Author Damien Cauquil

Category Reverse-Engineering

Tags hardware, tool, open-source, reverse-engineering, binary analysis, release, 2022

In this blogpost we present our brand new version of binbloom, a tool to find the base address of any 32 and 64-bit architecture firmware, and dig into the new method we designed to recover this grail on both of these architectures.

Introduction

Reverse-engineering hardware devices usually requires extracting data from memory, be it from an internal Flash of a SoC, an external NAND or SPI flash chip. Extracting memory content is part of the job, but once done we still need to analyze it and face the inevitable truth: we may be in front of an unknown memory dump or just have no idea of how information is stored in it, how it is loaded into the SoC or MCU memory and more generally where we can find interesting data and code. If you are into MCU/SoC firmware reverse-engineering this should sound familiar, as embedded Linux or other operating systems mostly rely on filesystems that can be identified and recovered with well-known tools.

These firmwares are strongly tied to a specific architecture that uses a given processor with its own peripherals and communication buses, with its own characteristics and specificities, making reverse-engineering a tedious task. This information may be found in the architecture documentation, when available. As a matter of fact, we need dedicated tools to quickly find some specific information before loading a firmware into our preferred disassembler:

architecture endianness, because it is better to know how values are stored in memory (and by the way how instructions are decoded);

the base address at which the firmware content is loaded (if the firmware is not a collage of various blocks of data and code).

Moreover, it could also be interesting to automatically detect interesting structures or arrays of structures such as the ones used to store Unified Diagnostic Services message IDs and related functions addresses for instance (these structures are very common in automotive ECU firmwares).

Guessing endianness

The endianness refers to the way integer values are stored in memory: least-significant byte first (little-endian) or most-significant byte first (big-endian, also known as network byte order). Guessing the endianness of an unknown firmware is not straightforward, but most of the existing tools consider these two options and try to determine which one gives the best results. There is no real alternative to this approach, and results are usually pretty good. Moreover, if you know the architecture your firmware is supposed to run on then you may know what endianness it supports (or not, e.g. ARM processors that handle both). Anyways, it is no big deal to figure out which one is used.

Finding a firmware base address

A firmware is usually mapped at a specific address in memory, depending on the architecture and its configuration. It could be loaded by a bootloader and stored at a particular address in RAM, or even be transparently mapped in memory and accessed through a dedicated bus. Supposing we do not know this address, how would we guess it based on what we have? We can only rely on information stored in the firmware, and based on this we would determine the most probable loading address.

Most of the existing tools like rbasefind, basefind.py, basefind.cpp, or even binbloom v1 try to find valuable data in the content of a firmware, such as text strings or pointers, and use them to recover the base address with more or less success. These methods will be detailed later in this blog post, as well as their pros and cons. The fact is we have tools that are able to guess or recover the base address of a given firmware, unless you have to deal with a 64-bit architecture such as AArch64 or there is no text strings in it. There is no magical tool, and the ones we use also have some flaws and limitations.

Issues and limitations

These tools cannot handle 64-bit firmwares because they were not designed to support them. They are also heavily dependent on the type of data stored inside the firmware, since it is the only input they can use to guess the corresponding base address. You have a firmware with no text strings and a few kilobytes of data? Don't expect too much, as a statistical analysis performed on a few kilobytes may not produce any reliable output.

The way pointers are determined by these tools is also a weakness, especially when a firmware contains more data than code. In this case, some 32-bit values may be considered as valid pointers whereas they only belong to some data stored in the firmware, thus introducing a bias in any statistical analysis and eventually leading to the wrong base address.

Nevertheless, the existing tools work pretty well for most of the 32-bit firmware files and memory dumps extracted from usual devices (well-known architecture used with well-known compiler). They are able to find one or more potential base addresses in most of the cases.

Guessing a firmware base address (on 32-bit architectures)

Searching for the base address of a given firmware or memory dump is not trivial and can be solved in different ways:

we can try all the possible base address values and try to determine which one gives the maximum number of valid pointers;

we can infer the base address from valid pointers present in the firmware.

Let's review these techniques based on real tools and determine the pros and cons for each of them.

Brute-forcing base address

The first one that comes to mind is the one that has been implemented in rbasefind. This technique is really simple as we only need to iterate over every possible base address (there are 4,294,967,295 of them) and check for each potential pointer found in this firmware if it points to a known text string present in the firmware. It allows us to compute a score for each candidate, and to filter them in order to get the best candidate (the one with the best score, i.e. the one for which we have found the greatest number of pointers pointing to actual text strings).

rbasefind implements this technique by first looking for text strings and referencing them, and then searching for valid pointers by iterating over all possible base addresses. This technique is really effective for firmwares with enough text strings. A similar approach is implemented in the first version of binbloom when provided with a list of function addresses, rather than letting the tool look for text strings. binbloom then counts unique pointers for each base address candidate, and considers the one with the best score as the most probable base address.

Inferring base address from pointers

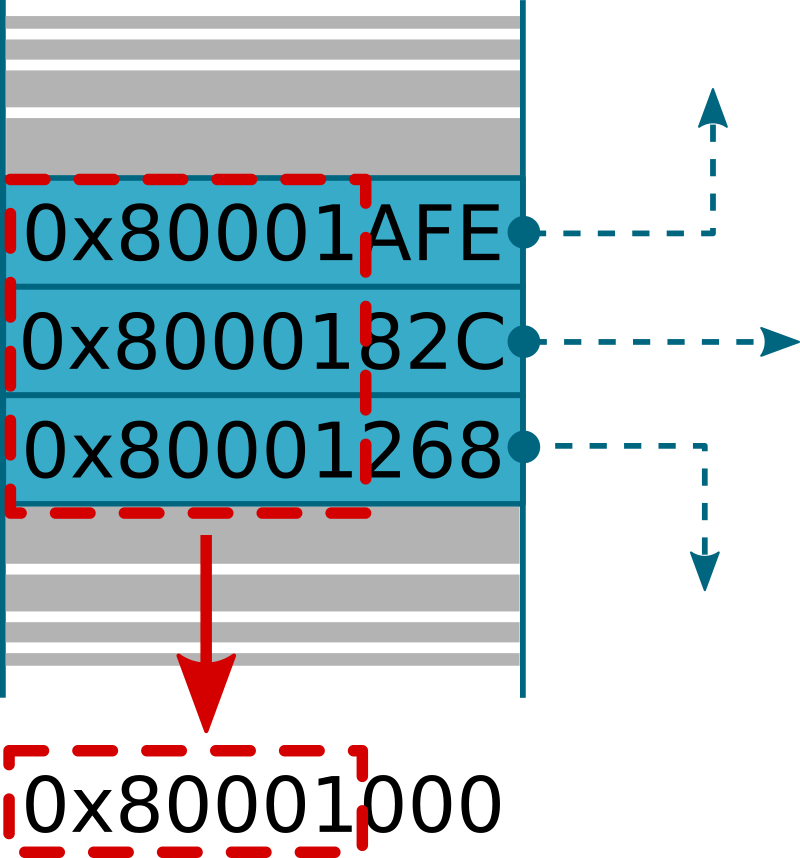

Another way of finding a firmware base address is to infer it from pointers that are stored in memory. Multiple valid pointers may share the same most-significant bits as they point to the same memory region, so if we loop over each pointer candidate that may be stored in a firmware and keep the first similar most significant bits, we may deduce the base address or at least some of its most significant bits.

As shown in the above image, pointers may have the same most-significant bits, in this case bits 11 to 31, that may be useful to deduce the corresponding base address (0x80001000). This technique is less reliable than the first one introduced in this section, as some bits may be missing (but in any case we should be very close to the correct address).

Extending these techniques to support 64-bit architecture firmwares

Implementing the same brute-force technique with 64-bit applications is another story, as the number of candidates will grow from 4,294,967,295 to 35,184,372,088,831 addresses (considering a 47-bit user space address and a page size of 4 bytes when dealing with a 64-bit architecture), which is huge and will take ages to test. However, inferring base address from pointers is still a valid option for 64-bit firmwares, as we may consider 64-bit pointers and search for similar most-significant bits. This technique is not as efficient as the previous one, but may be a good starting point.

It could also be interesting to find an alternative to the first technique that would not require testing every possible value to determine the correct base address. This was the subject of our research that led to the development of binbloom v2 which is detailed in the following section.

Designing a unified method for 64-bit architectures

Since brute-force is no longer an option, we need to determine an alternative way to find a 64-bit application code base address. First, let us summarize what is inside a classic firmware file or memory dump extracted from external storage:

blocks of code containing a set of functions;

blocks of data containing data used by functions;

blocks of unused data or simply empty storage space required for alignment.

Data include text strings, values, arrays of values, structures, anything required by the code to run properly and store data in a structured manner. One can also find references to data inside a data block, such as one or more pointers that point to one or more specific locations where other data are stored. These pointers are very interesting because they are based on the firmware base address with a specific displacement (called offset), and can be used to find the base address as demonstrated above. Problem is, we don't know how to differentiate a pointer from other types of data stored in the firmware!

Distinguishing code and data

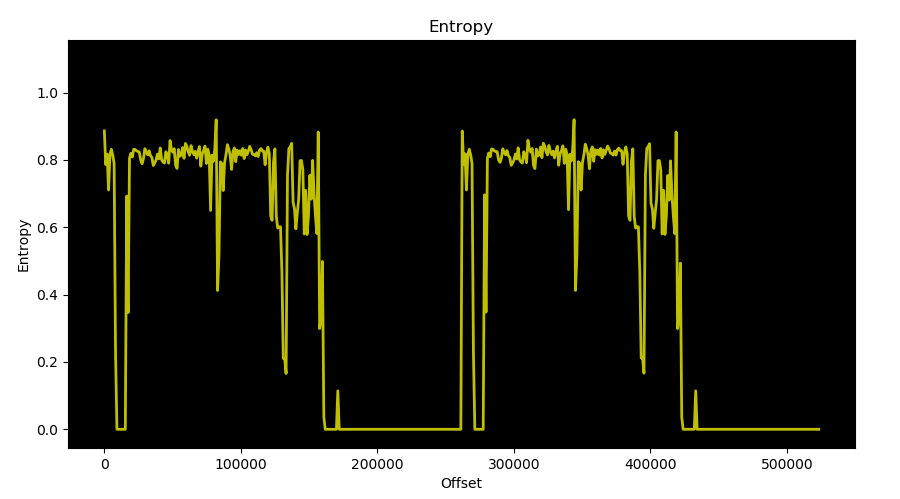

In order to avoid false positives we need to focus on data blocks and the information they contain. Data blocks can be identified thanks to Shannon entropy: a data block entropy is considered to be between 0 and 0.5, and this is a totally arbitrary value based on a set of firmware files we have already analyzed, related to known architectures. Code blocks usually have an entropy between 0.6 and 0.8 (again, based on our observations) and this could vary depending on the architecture (see o-glasses: Visualizing X86 Code From Binary Using a 1D-CNN for another example of entropy-based data classification). Entropy is used here as a heuristic value to tell code and data blocks apart, to focus on the latter when searching for candidate base addresses. The following image shows the result of an analysis performed on a firmware:

One can notice this firmware is composed of two identical blobs with the same entropy pattern, this is often the case when a device uses an A/B update scheme: it allows the device to recover from a failed firmware upgrade. Relying on entropy is also very helpful to determine what type of data a hypothetical pointer may point to. It gives valuable information on this pointer, and therefore on the candidate base address it relates to.

Picking up candidates instead of brute-forcing them

If we identify a text string in a firmware, we can legitimately suppose there is a reference to this text string, somewhere in a code or data block. Code blocks are made of instructions that may use an offset from the location of the instruction to compute the location of the referenced text string, so we cannot expect to find a pointer stored as-is in a code block. However, if a pointer to a specific text string is stored in a data block then it would be really significant (and more probable). Based on this observation, we can consider each 64-bit value from the target firmware as a pointer to a previously identified text string, and compute a candidate base address. We can repeat this for all the text strings and all the 64-bit values present in every data block, and we will end up with a list of candidates for our base address! Moreover, we can count the number of times each candidate base address appears, and store it along with these candidates.

To illustrate this method, let's consider the following piece of firmware (for clarity purpose, 64-bit values referenced in the following example are truncated to 32 bits):

0x010070: "Hello world !"

...

0x01007F: "This is a demo"

...

0x020304: 0x000000008003007F

0x02030C: 0x0000000080030070

Two text strings are present: "Hello world !" at offset 0x010070 and "This is a demo" at offset 0x01007F. We also have two different values at offsets 0x020304 and 0x02030C, respectively 0x8003007F and 0x80030070. We then consider the value 0x8003007F to be a 64-bit pointer onto the first text string, meaning this text string should be located at address 0x8003007F in memory while residing at offset 0x010070 in our firmware. In this case, the base address should be 0x8003007F - 0x010070, which gives 0x8002000F. However, in the case it points to the second text string, the base address should be 0x8003007F - 0x01007F, which gives 0x80020000. We do the same for the second 64-bit value and find two possible base addresses: 0x8001FFF1 and 0x80020000.

By doing so, we establish a list of candidate base addresses with an associated value (number of occurrences) that may be considered as a score:

0x8001FFF1 with a score of 1

0x80020000 with a score of 2

0x8002000F with a score of 1

We end up with three base address candidates, except we will not cover all the possible values (but remember, we cannot test all the possibilities as it would take ages). Candidate base addresses with the highest scores are more likely to be the base address we are looking for, others may also be of interest and we cannot discard them as we may have false positives. In this example, 0x0000000080020000 seems to be a good base address candidate.

This technique is faster than enumerating all possible base addresses, but it also has a drawback: the bigger the firmware, the bigger the memory footprint. And memory management is one of the main issues we had to solve in order to have good performances.

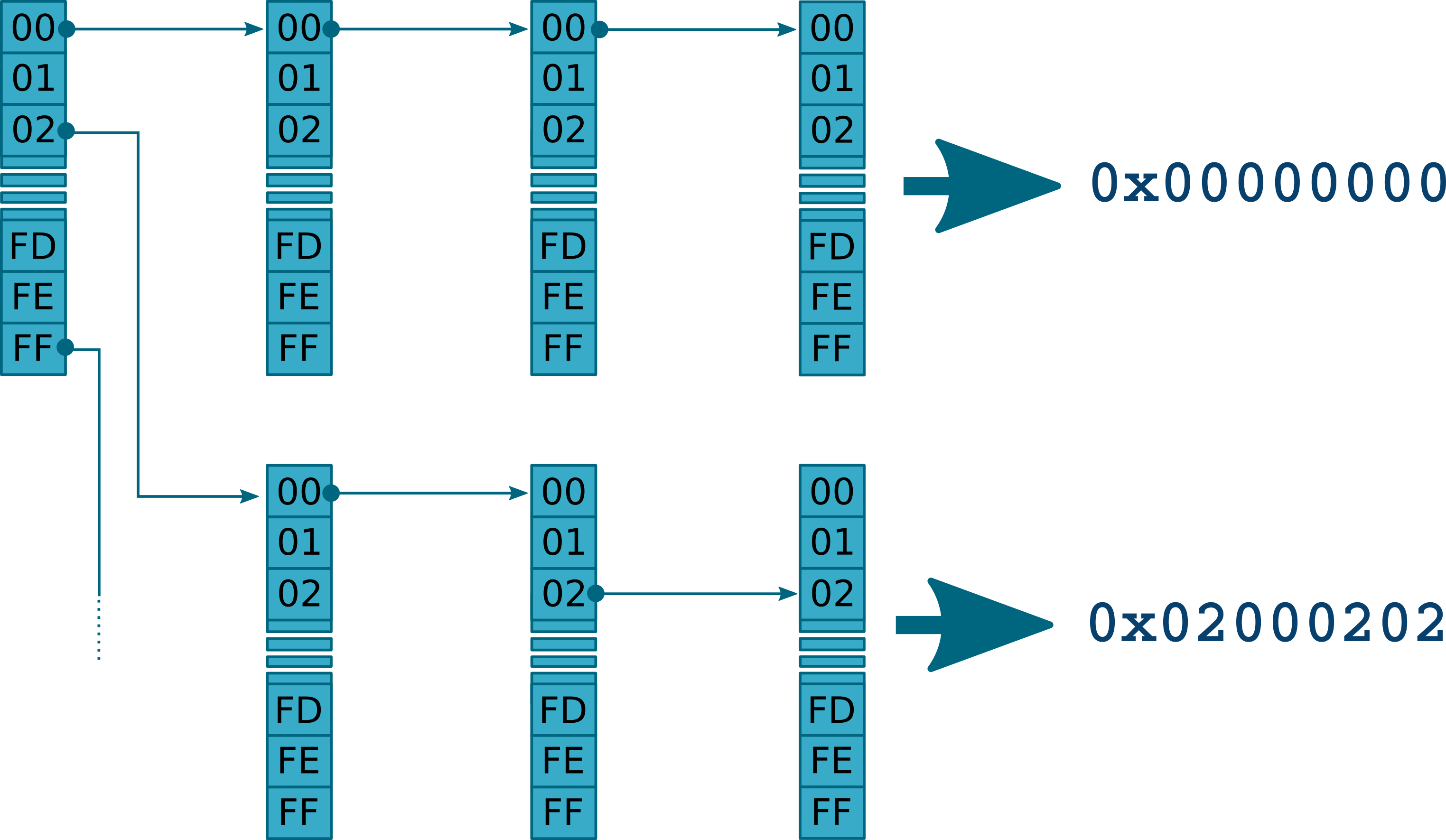

Optimizing memory and performance

All candidate base addresses must be stored in memory to count the number of times they appear, but this must be done efficiently. Using a linked list is out of question as we will not be able to search for a given address in a constant time. Using a hash map could be interesting, but it will be difficult to do statistics on a range of addresses, i.e. on a set of items. After having reviewed the different storage paradigms, we decided to use a tree to store the candidate base addresses. In this tree, each node stores 8 bits of a candidate address, from the most significant byte to the least significant byte. The tree leaves store the final count for complete addresses, allowing us to compute a score for address ranges as well as individual addresses. The following image shows what the structure looks like (representing the last 4 layers for 32-bit addresses).

This also allows for constant complexity while searching for a 64-bit address: we only need 8 operations to get the information we need. Search complexity goes from to , which drastically improves the efficiency of our algorithm.

This tree will grow as we are collecting candidate base addresses, until it reaches a point where it requires too much memory. When it happens we prune the tree to only keep the best leaves, i.e. the addresses with the highest scores, freeing as much memory as possible and making room for new candidates. Using this tree allows flexible memory usage while keeping tracks of best candidates.

Points of interest

For each candidate base address found, we count the number of valid references to points of interests we can find within the firmware content. A point of interest is an element in the firmware content that is significant and that can be identified, such as a text string, an array of similar values or a code block. If we find a lot of pointers that point to some valid points of interest considering a candidate base address, then it means this address may be the one we are looking for and its score will increase. Based on entropy, we can distinguish function pointers and data pointers. Pointers on text strings are quite easy to determine, contrary to arrays pointers.

Moreover, if we stumble upon an array of pointers with all pointers considered valid for a specific candidate base address, this will drastically increase its score as it is highly probable that this base address is the one we are looking for.

Summary of this new method

The proposed unified method follows these different steps:

analyze firmware's content: compute entropy, determine code and data blocks, search for points of interest (text strings and arrays of similar values) in data blocks;

generate an ordered tree of candidate base addresses, considering each 64-bit value from the firmware content as a potential pointer onto a point of interest;

for each candidate address, consider the number of valid pointers (i.e. pointers pointing on points of interest) and compute a score;

display top 10 candidates from highest score to lowest score.

This technique is quite efficient, and can also be used on a 32-bit architecture firmware as 32-bit addresses may be extended to 64 bits.

Searching for structured data

The first mandatory step of our proposed method relies on finding potential points of interest that can be verified once we have guessed the base address. With this base address and a list of points of interest in hand, it is tempting to try to identify logically structured data inside a firmware.

Identifying arrays of structures and other types of data

Structures are made of various types of data, but some of them are very common and could be identified. Function pointers and text string pointers, as demonstrated before, are quite easy to determine once we know the base address. But identifying structures is another story, as we need multiple items that follow a specific structure to perform a comparison and then be able to determine a structure pattern.

Luckily, a lot of programming patterns rely on structure arrays, especially in embedded devices Software Development Kits (SDK). If an embedded software needs to dispatch calls to specific function handlers based on an integer value, or simply using a list of drivers or other items that are stored statically in flash, it will most of the time end up using an array of a specific structure that holds all the required information. This is also the case in automotive embedded systems, as some protocol stacks need to parse messages and call a set of corresponding functions to handle different messages or packets. For instance, some Unified Diagnostic System (UDS) protocol stacks rely on specific message IDs to determine which function should be called to handle them, in what is usually called a UDS database.

Identifying structure arrays requires to find a series of structures that share the same types of values at the same offsets, thus corresponding to a specific pattern. Finding this pattern also requires to figure out the base structure size, offsets and corresponding types. Once this structure pattern identified, its members may be analyzed and this array of structures becomes a new point of interest as well.

Automatic structure arrays recognition and annotation

This feature is implemented in binbloom v1 and gives pretty good results, even if it focuses on UDS message IDs only. In binbloom v2, we have implemented a more generic detection algorithm that searches for every possible array of structures but restricted it to UDS database search for this first release. It gave pretty good results so far, but we consider that it may be improved in a future release. It could be interesting to make this feature compatible with usual disassemblers and debuggers such as IDA Pro, Ghidra or Radare2, by allowing automatic structure declaration and code annotation if possible.

Introducing Binbloom v2

Features

Binbloom v2 implements this new base address recovery technique and UDS database lookup that supports both 32-bit and 64-bit firmwares. It has been tested against a set of various firmware files designed for various architectures and gave pretty decent results and performances.

Binbloom v2 provides the following features:

endianness guessing;

base address guessing supporting 32-bit and 64-bit architectures;

UDS database search.

We performed a benchmark of binbloom v1, binbloom v2 and rbasefind on a set of various firmware files to see if they are able to guess their endianness and recover the corresponding base addresses:

| Firmware | Endianness | Size (in bytes) |

|---|---|---|

| AE5R100V | 32 | 1048576 |

| bootloader ARM | 32 | 143360 |

| ECU external flash firmware | 32 | 2162688 |

| IntegrityOS application | 64 | 327680 |

| UBoot standalone application | 32 | 2883584 |

| STM32 firmware | 32 | 9132 |

| Teensy firmware | 32 | 20480 |

| Google Titan M firmware (2018) | 32 | 524288 |

| Google Titan M firmware (2019) | 32 | 524288 |

| Google Titan M firmware (2021) | 32 | 524288 |

| Flash Air firmware | 32 | 2097152 |

Firmware endianness accuracy

Rbasefind is not able to guess endianness and therefore is not present in the table below.

| Firmware | Binbloom v1 | Binbloom v2 |

|---|---|---|

| AE5R100V | yes | yes |

| bootloader ARM | no | no |

| ECU external flash firmware | yes | yes |

| IntegrityOS application | ~ | yes |

| UBoot standalone application | yes | yes |

| STM32 firmware | no | no |

| Teensy firmware | yes | yes |

| Google Titan M firmware (2018) | yes | yes |

| Google Titan M firmware (2019) | yes | yes |

| Google Titan M firmware (2021) | yes | yes |

| Flash Air firmware | yes | yes |

Base address search accuracy

Base address search accuracy has been evaluated as the ranking of the correct base address in the base addresses list returned by the tested tool.

| Firmware | Binbloom v1 | Binbloom v2 | rbasefind |

|---|---|---|---|

| AE5R100V | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| bootloader ARM | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| ECU external flash firmware | ~ | 1 | 1 |

| IntegrityOS application | ~ | 1 | ~ |

| UBoot standalone application | ~ | 1 | 3 |

| STM32 firmware | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Teensy firmware | ~ | 1 | 1 |

| Google Titan M firmware (2018) | ~ | 1 | 1 |

| Google Titan M firmware (2019) | ~ | 1 | 1 |

| Google Titan M firmware (2021) | ~ | 1 | 1 |

| Flash Air firmware | 2 | 1 | 1 |

Binbloom v2 seems to give more accurate results than binbloom v1 and rbasefind for the considered firmwares.

Processing time comparison (in seconds)

The following benchmark has been performed on a Lenovo T480 laptop, using best options for each tool (with a maximum of 8 concurrent threads for Binbloom v2 and rbasefind).

| Firmware | Binbloom v1 | Binbloom v2 | rbasefind |

|---|---|---|---|

| AE5R100V | 11.33 | 3.019 | 0.916 |

| bootloader ARM | 5.48 | 0.183 | 5.40 |

| ECU external flash firmware | 5.78 | 5.69 | 6.17 |

| IntegrityOS application | ~ | 1.453 | ~ |

| UBoot standalone application | 8.228 | 0.723 | 1.462 |

| STM32 firmware | 5.232 | 0.03 | 0.064 |

| Teensy firmware | 5.686 | 0.068 | 0.053 |

| Google Titan M firmware (2018) | 9.664 | 1.288 | 10.23 |

| Google Titan M firmware (2019) | 9.46 | 1.324 | 10.095 |

| Google Titan M firmware (2021) | 9.485 | 1.64 | 11.240 |

| Flash Air firmware | 11.042 | 37.52 | 44.184 |

Binbloom v2 seems to be the fastest tool and has been successfully tested on the following architectures:

32-bit and 64-bit ARM

Tensilica Xtensa

MIPS

Renesas SH-2E 32-bit

Toshiba MeP-c4

There is still room for improvement

This version 2 of binbloom introduces a new approach to find base addresses of unknown firmware dumps for both 32-bit and 64-bit architectures, but still has room for improvement.

First, determining memory region types based on entropy may vary from one architecture to another, as the thresholds used by binbloom are generic and may not be accurate for some specific architectures.

We are actually considering implementing a function prologue detection routine for most common architectures in order to quickly identify function pointers, based on an existing disassembler library (like capstone) if possible. This could make function identification more reliable and therefore function pointer identification easier.

Second, binbloom v2 still relies on the end user to provide information about the target architecture base data size (32 or 64 bits), while it may be able to determine this by itself, as it actually does for endianness. Again, this would require to experiment some algorithms to quickly determine this information without having to analyze a whole firmware file.

Last but not the least, our latest tests showed that our implementation of structure array identification reports some false positives and must be considered as experimental even if it is used to determine UDS database locations. It definitely requires more work and testing to be used on a regular basis for all types of structures.

Download, test and contribute to Binbloom

Binbloom source code is available on github and comes with some examples in its readme file and manpage (once installed). Feel free to give it a try, report issues and send pull requests! If you want to share some specific firmware files that may help improving binbloom, please open an issue or ping me.