Author Adrien Guinet

Category Programming

Tags C, C++, memory, programming, 2018

CPUs used to perform better when memory accesses are aligned, that is when the pointer value is a multiple of the alignment value. This differentiation still exists in current CPUs, and still some have only instructions that perform aligned accesses. To take into account this issue, the C standard has alignment rules in place, and so the compilers exploit them to generate efficient code whenever possible. As we will see in this article, we need to be careful while casting pointers around to be sure not to break any of these rules. The goal of this article is to be educative by showcasing the problem and by giving some solutions to easily get over it.

For people that just want to see them and the final code, you can go directly to the library section.

Spoiler: the provided solutions have nothing really disruptive, and are fairly standard ones! Other resources on the Internet [1] [2] also cover this issue.

The problem

Let's consider this hash function, that computes a 64-bit integer from a buffer:

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

static uint64_t load64_le(uint8_t const* V)

{

#if !defined(__LITTLE_ENDIAN__)

#error This code only works with little endian systems

#endif

uint64_t Ret = *((uint64_t const*)V);

return Ret;

}

uint64_t hash(const uint8_t* Data, const size_t Len)

{

uint64_t Ret = 0;

const size_t NBlocks = Len/8;

for (size_t I = 0; I < NBlocks; ++I) {

const uint64_t V = load64_le(&Data[I*sizeof(uint64_t)]);

Ret = (Ret ^ V)*CST;

}

uint64_t LastV = 0;

for (size_t I = 0; I < (Len-NBlocks*8); ++I) {

LastV |= ((uint64_t)Data[NBlocks*8+I]) << (I*8);

}

Ret = (Ret^LastV)*CST;

return Ret;

}

The full source code with a convenient main function can be downloaded here: https://gist.github.com/aguinet/4b631959a2cb4ebb7e1ea20e679a81af.

It basically processes the input data as blocks of 64-bit little endian integers, performing a XOR with the current hash value and a multiplication. For the remaining bytes, it fills a 64-bit number with the remaining bytes.

If we want to make this hash portable across architectures (portable in the sense that it will generate the same value on every possible CPU/OS), we need to take care of the target's endianness. We will come back on this topic at the end of this blog post.

Let's compile and run this program on a classical Linux x64 computer:

$ clang -O2 hash.c -o hash && ./hash 'hello world'

527F7DD02E1C1350

Everything runs smoothly. Now, let's cross compile this code for an Android phone with an ARMv5 CPU in Thumb mode and run it. Supposing ANDROID_NDK is an environment variable that points to an Android NDK installation, let's do this:

$ $ANDROID_NDK/build/tools/make_standalone_toolchain.py --arch arm --install-dir arm

$ ./arm/bin/clang -fPIC -pie -O2 hash.c -o hash_arm -march=thumbv5 -mthumb

$ adb push hash_arm /data/local/tmp && adb shell "/data/local/tmp/hash_arm 'hello world'"

hash_arm: 1 file pushed. 4.7 MB/s (42316 bytes in 0.009s)

Bus error

Something went wrong. Let's try another string:

$ adb push hash_arm && adb shell "/data/local/tmp/hash_arm 'dragons'"

hash_arm: 1 file pushed. 4.7 MB/s (42316 bytes in 0.009s)

39BF423B8562D6A0

Debugging

If we grep the kernel logs for details, we have:

$ dmesg |grep hash_arm [13598.809744] [2: hash_arm:22351] Unhandled fault: alignment fault (0x92000021) at 0x00000000ffdc8977

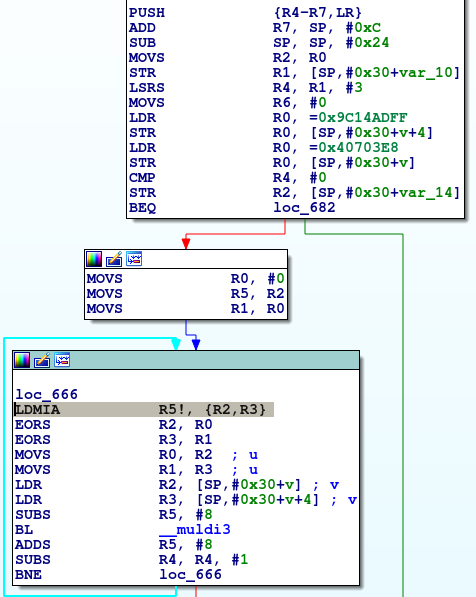

It looks like we have issues with alignment. Let's look at the assembly generated by the compiler:

The LDMIA instruction is loading data from memory into multiple registers. In our case, it loads our 64-bit integer into two 32-bit registers. The ARM documentation of this instruction [3] states that the memory pointer must be word-aligned (a word is 2 bytes in our case). The problem arises because our main function uses a buffer passed by the libc loader to argv, which has no alignment guarantees.

Why does this happen?

The question we can naturally ask is why does the compiler emits such an instruction? What makes him/her/it think the memory pointed by Data is word-aligned?

The problem happens in the load64_le function, where this cast is happening:

uint64_t Ret = *((uint64_t const*)V);

According to the C standard [10]: "Complete object types have alignment requirements which place restrictions on the addresses at which objects of that type may be allocated. An alignment is an implementation-defined integer value representing the number of bytes between successive addresses at which a given object can be allocated." In other words, this means that we should have:

V % (alignof(uint64_t)) == 0

Still according to the C standard, converting a pointer from a type to another without respecting this alignement rule is undefined behavior (http://www.open-std.org/jtc1/sc22/wg14/www/docs/n1570.pdf page 74, 7).

In our case the alignment of uint64_t is 8 bytes (which can be checked for instance like this https://godbolt.org/z/SJjN9y ), hence we are experiencing this undefined behavior. What happens more precisely here is that the previous cast directly said to our compiler "Ret is a multiple of 8, and so a multiple of 2. You are safe to use LDMIA".

The problem does not arise under x86-64 because the Intel mov instruction supports unaligned loads [4] (if alignment checking is not enabled [5], which is something that can only be enabled by operating systems [6]). This is why a non negligible part of "old" code have this silent bug, because they never showed up on x86 computers (where they have been developed). It's actually so bad that the ARM Debian kernel has a mode to catch unaligned access and handle them properly [7]!

Solutions

Multiple loads

One classical solution is to "manually" generate the 64-bit integer by loading it from memory byte by byte, here in a little-endian fashion:

uint64_t load64_le(uint8_t const* V)

{

uint64_t Ret = 0;

Ret |= (uint64_t) V[0];

Ret |= ((uint64_t) V[1]) << 8;

Ret |= ((uint64_t) V[2]) << 16;

Ret |= ((uint64_t) V[3]) << 24;

Ret |= ((uint64_t) V[4]) << 32;

Ret |= ((uint64_t) V[5]) << 40;

Ret |= ((uint64_t) V[6]) << 48;

Ret |= ((uint64_t) V[7]) << 56;

return Ret;

}

This code has multiple advantages: it's a portable way to load a little endian 64-bit integer from memory, and does not break the previous alignment rule. One drawback is that, if we just want the natural byte order of the CPU for integers, we need to write two versions and compile the good one using ifdef's. Moreover, it's a bit tedious and error-prone to write.

Anyway, let's see what clang 6.0 in -O2 mode generates, for various architectures:

x86-64 : mov rax, [rdi] (see https://godbolt.org/z/bMS0jd ). This is what we would expect, as the mov instruction on x86 supports non-aligned access.

ARM64 ldr x0, [x0] (https://godbolt.org/z/qlXpDB ). Indeed, the ldr ARM64 instruction does not seem to have any alignment restriction [8].

ARMv5 in Thumb mode: https://godbolt.org/z/wCBfcV. This is basically the code we wrote, which loads the integer byte by byte and constructs it. We can note that this is some non negligible amount of code (compared to the previous cases).

So Clang is able to detect this pattern and to generate efficient code whenever possible, as long as optimisations are activated (note the -O1 flag in the various godbolt.org links)!

memcpy

Another solution is to use memcpy:

uint64_t load64_le(uint8_t const* V) {

uint64_t Ret;

memcpy(&Ret, V, sizeof(uint64_t));

#ifdef __BIG_ENDIAN__

Ret = __builtin_bswap64(Ret);

#endif

return Ret;

}

The advantages of this version are that we still don't break any alignment rule, it can be used to load integers using the natural CPU byte order (by removing the call to __builtin_bswap64), and is potentially less error-prone to write. One disadvantage is that it relies on a non-standard builtin (__builtin_bswap64). GCC and Clang support it, and MSVC has equivalents: https://msdn.microsoft.com/fr-fr/library/a3140177.aspx.

Let's see what clang 6.0 in -02 mode generates, for various architectures:

x86-64: mov rax, [rdi] (https://godbolt.org/z/5YKLHE). This is what we would expect (see above)!

ARM64: ldr x0, [x0] (https://godbolt.org/z/2TaFIy)

ARMv5 in Thumb mode: https://godbolt.org/z/3dX7DY (same as above)

We can see that the compiler understands the semantic of memcpy and optimizes it correclty, as alignment rules are still valid. The generated code is basically the same as in the previous solution.

Helper C++ library

After having written that kind of code a dozen times, I've decided to write a small header-only C++ helper library that allows the loading/storing in natural/little/big byte order for integers of any type. It's available on github here: https://github.com/aguinet/intmem. Nothing really fancy, but it might help and/or save time to others.

It has been tested with Clang and GCC under Linux (x86 32/64, ARM and mips), and with MSVC 2015 under Windows (x86 32/64).

Conclusion

It's a bit sad that we still need to do this kind of "hacks" to write portable code to load integers from memory. The current status is bad enough that we need to rely on compilers' optimisations to generate efficient and valid code.

Indeed, compiler people like to say that "you should trust your compiler to optimize your code". Even if this is generally an advice to follow, the big problem of the solutions we described is that they do not rely on the C standard, but on modern C compiler optimisations. Thus, nothing enforces them to optimize our memcpy call or the list of binary ORs and shifts of the first solution, and a change/bug in any of these optimisations could render our code inefficient. Looking at the code generated in -O0 gives an idea of what this code could be (https://godbolt.org/z/bUE1LP).

In the end, the only way to be sure that what we expect actually happened is by looking at the final assembly, which is not really practical in real-life projects. It could be nice to have a better automated way to check for this kind of optimisations, for instance by using pragma s, or by having a small subset of optimisations that could be defined by the C standard and activated on demand (but the questions are: which one? how to define them?). Or we could even add a standard portable builtin to the C language to do this. But that's for another story...

On a somehow related matter, I would also suggest reading an interesting article by David Chisnall about why C isn't a low-level language [9].

Acknowledgment

I'd like to thank all my Quarkslab colleagues that took time to review this article!

References

| [1] | http://pzemtsov.github.io/2016/11/06/bug-story-alignment-on-x86.html |

| [2] | https://research.csiro.au/tsblog/debugging-stories-stack-alignment-matters/ |

| [3] | http://infocenter.arm.com/help/index.jsp?topic=/com.arm.doc.dui0068b/BABEFCIB.html |

| [4] | https://www.intel.com/content/dam/www/public/us/en/documents/manuals/64-ia-32-architectures-software-developer-instruction-set-reference-manual-325383.pdf , page 690 |

| [5] | https://xem.github.io/minix86/manual/intel-x86-and-64-manual-vol3/o_fe12b1e2a880e0ce-231.html |

| [6] | No x86 operating system that I know of activates this. One would not that doing so could make compilers generate bad code, if they are not aware of it! |

| [7] | https://wiki.debian.org/ArmEabiFixes#word_accesses_must_be_aligned_to_a_multiple_of_their_size |

| [8] | http://infocenter.arm.com/help/index.jsp?topic=/com.arm.doc.dui0802b/LDR_reg_gen.html |

| [9] | https://queue.acm.org/detail.cfm?id=3212479 |

| [10] | http://www.open-std.org/jtc1/sc22/wg14/www/docs/n1570.pdf, page 66, 6.2.8.1 |