Author Eduardo Blazquez

Category Programming

Tags java, obfuscation, programming, 2026

In this article I describe Java bytecode obfuscation, using one of the challenges I did in 2023 as part of the interviews with Quarkslab for the position of Java compiler engineer in QShield.

Introduction

In the middle of my PhD back in 2023, I was writing a static analysis tool for Android's Dalvik EXecutable Format and someone from the LLVM community recommended that I talk about the topic at the EuroLLVM conference dedicated to the LLVM compilation framework, because my analysis tool used part of this framework as an Intermediate Representation. After this conference, someone recommended that I apply for a Java Compiler Engineer position in Quarkslab's Qshield team, to develop obfuscations for Java, and in Java...

Transforming Java Bytecode

As part of the interview process, one of the tasks was to write a simple obfuscation for Java bytecode. Having previously written a disassembler for Android Dalvik bytecode, I thought I could quickly learn about Java bytecode and how to manipulate it for obfuscation purposes. One of the requirements was to use the ASM library, which is specifically designed for Java bytecode analysis and manipulation. The obfuscation technique to implement was opaque predicates. Before diving into the opaque predicate implementation, this section covers the necessary background on three topics: Java bytecode, comparisons between bytecode and assembly, and the ASM library.

Java bytecode

Java is an object-oriented language which is mostly intended to write once, run everywhere, in opposite to other languages like C or C++ that are compiled for a specific architecture (the code is translated to a binary representation for a processor architecture). In Java, the code is compiled to an intermediate representation (also known as bytecode) that can be run on any device hosting a Java Virtual Machine. This Java Virtual Machine translates the Java bytecode to instructions designed for the host architecture while running.

The bytecode itself is a sequence of instructions designed for a stack-based virtual machine. Each instruction consists of a one-byte opcode followed by zero or more operands (this makes the Java Bytecode instruction set very small compared with some computer architectures like x86). The JVM specification defines around 200 opcodes, though not all byte values are currently used. These instructions operate on a few key data areas: the operand stack (where most operations happen), local variables, and the constant pool.

Let's look at a simple example. Consider this Java method:

public int add(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

It compiles to the following bytecode:

0: iload_1

1: iload_2

2: iadd

3: ireturn

The iload_1 and iload_2 instructions push the first and second integer parameters (these are retrieved from the local variables previously mentioned, where local 0 is usually used for the this object) onto the operand stack. The iadd instruction pops these two values, adds them, and pushes the result back. Finally, ireturn returns the integer value from the top of the stack.

public int max(int a, int b) {

if (a > b) {

return a;

} else {

return b;

}

}

Compiles to:

0: iload_1

1: iload_2

2: if_icmple 7

5: iload_1

6: ireturn

7: iload_2

8: ireturn

The control flow is handled by if_icmple (if integer compare less than or equal), which compares the two values on the stack and jumps to bytecode offset 7 if the condition is true. Notice how the conditional jump targets are explicit bytecode offsets, making the control flow graph straightforward to reconstruct. The stack operations (iload_1, iload_2) and typed comparisons (if_icmple specifically for integers) make it clear what is being compared and how.

Java bytecode has explicit control-flow instructions and uses a stack-based architecture for parameter passing. Additionally, Java bytecode includes type information that is preserved during compilation. These characteristics make it significantly easier to disassemble and decompile compared to native machine code—decompilers can leverage the type metadata and structured control flow to reconstruct high-level Java source code with accuracy. For this reason, obfuscating Java bytecode before releasing a Java-based product is important if we want to prevent our code from being easily analyzed.

Bytecode vs Assembly: Key Differences

Execution model: Assembly uses registers from the processor directly (like eax, ebx in x86), while Java bytecode operates on a virtual stack from the Java Virtual Machine. In assembly, we explicitly move data between registers; in bytecode we push and pop from the virtual stack.

Portability: Assembly is architecture-specific (e.g. ARM code won't run on x86). Bytecode runs anywhere the JVM is available.

Memory access: Assembly provides direct memory access with pointers and addresses. Bytecode abstracts this away, we work with object references and array indices, with bounds checking built in, etc.

Verification: Bytecode is designed to be verifiable before execution. The JVM can check type safety and ensure code won't perform illegal operations (this is one of the main issues when writing Java bytecode obfuscation). Assembly has no such guarantees.

Pros of bytecode: - Platform independent - Safer (built-in bounds checking, no raw pointers) - Closer to source code structure

Cons of bytecode: - Easier to reverse engineer (higher abstraction level) - Runtime overhead (though JIT compilation helps) - Less control over low-level optimizations - Dependent on JVM implementation - Larger binary size compared to native code

From a reverse engineering perspective, a non-protected bytecode is generally easier to analyze, even open source tools like Jadx do a great job recovering the original program structure with good accuracy. But for stripped native binaries, this process requires significantly more effort, and sometimes even professional tools are not able to accurately recover the original program structure.

The ASM Library

As previously mentioned, one of the requirements for this challenge was to use ASM, a library designed for Java bytecode manipulation. At the time, I had no experience with it. Fortunately, the library provides PDF documentation that, while somewhat outdated, proved really useful for understanding the fundamentals. Getting a printed copy and studying it over the weekend gave me a solid foundation to start the obfuscation project.

This Java library allows to work with Java bytecode in two different ways: the visitor pattern (the Core API) and the tree API.

With the visitor pattern (the Core API), we access every part of the bytecode using methods that we provide as visitors to that part of the bytecode. This way of manipulating the Java Bytecode is the fastest since every part can be manipulated and generated on the fly, and is also the one using the less memory since almost no information is stored: the information is processed and can be translated to bytecode as soon as processing is over.

The Core API works by calling a series of visit methods in a specific order as it encounters each element of a class file. When we want to read or modify bytecode, we create a ClassVisitor that implements callbacks for the different parts: visit() for class metadata, visitMethod() for each method, visitField() for fields, and so on. When visiting a method, we get a MethodVisitor that receives callbacks for each instruction: visitInsn() for simple instructions, visitVarInsn() for variable access, visitJumpInsn() for control flow, etc.

Here's a simple example that counts how many instructions are in each method:

class MethodInstructionCounter extends ClassVisitor {

public MethodInstructionCounter() {

super(ASM9);

}

@Override

public MethodVisitor visitMethod(int access, String name,

String descriptor, String signature,

String[] exceptions) {

return new MethodVisitor(ASM9) {

private int count = 0;

@Override

public void visitInsn(int opcode) {

count++;

super.visitInsn(opcode);

}

@Override

public void visitIntInsn(int opcode, int operand) {

count++;

super.visitIntInsn(opcode, operand);

}

@Override

public void visitVarInsn(int opcode, int var) {

count++;

super.visitVarInsn(opcode, var);

}

// ... other visitXxxInsn methods can be here

@Override

public void visitEnd() {

System.out.println("Method " + name + " has " + count + " instructions");

super.visitEnd();

}

};

}

}

In the previous code, we extend the ClassVisitor class, giving us access to all the methods needed to traverse the different parts of a class. The most important is access to the methods themselves, which allows us to count instructions. Inside the visitMethod method, when a new method is accessed, we return a MethodVisitor object. Like ClassVisitor, this is a class that provides all the methods for accessing the different instructions in the bytecode. By following this visitor pattern, we can traverse the code.

The main thing to understand here is that we're working in a streaming way. When visitInsn(IADD) is called, we're seeing an iadd instruction right at that moment. If we want to modify it, we need to decide immediately, we can't look ahead to see what comes next, and we can't easily look back at what came before. This makes certain transformations tricky, but it's what gives the Core API its speed and low memory footprint. We're essentially reading and writing the bytecode in a single pass.

Although this seems like a good approach to manipulate bytecode, this is not the best way to do it when writing a code protector and an obfuscation pipeline. Why? Because using the visitor API, we cannot access more data than the one from the visited component, or one globally stored in class fields. Also, even doing this, a code protector using this API would need to run twice, one for retrieving the information and another one for applying changes. To avoid this, and although it consumes more memory to keep the information, it is better to use the tree API.

The tree API offers Nodes to access the different bytecode elements, for example ClassNode or MethodNode to access classes and methods, and their components such as their name and flags for classes, or their instructions for methods. This API allows to access these objects through lists, and to modify their data. It also provides a ClassReader to load a class into a ClassNode and a ClassWriter to dump a class back to disk.

Here's an example of the Tree API similar to the previous one:

class MethodInstructionCounter {

public void countInstructions(byte[] bytecode) {

ClassReader cr = new ClassReader(bytecode);

ClassNode cn = new ClassNode();

cr.accept(cn, 0);

for (MethodNode method : cn.methods) {

int count = 0;

for (AbstractInsnNode insn : method.instructions) {

if (insn.getOpcode() >= 0) { // -1 means it's a pseudo-instruction like labels

count++;

}

}

System.out.println("Method " + method.name + " has " + count + " instructions");

}

// If we wanted to write the class back:

ClassWriter cw = new ClassWriter(ClassWriter.COMPUTE_FRAMES);

cn.accept(cw);

byte[] modifiedBytecode = cw.toByteArray();

}

}

The main advantage here is that the whole class structure is loaded in memory. As we can iterate in any way through the methods, and in the methods through the instructions, this approach allows us to build complex analyses and transformations that with the other API would require multiple passes over the same data.

Although ASM offers a nice API, this library provides only a very simple access to the bytecode structure. In case we would like to access data in a more abstract way as most compiler do (e.g. accessing the control-flow graph of a method), we would need to write dedicated analyses on top of ASM.

Implementing the Opaque Predicate Obfuscation

Now that we understand Java bytecode and the ASM library, let's implement the opaque predicate obfuscation. This section briefly covers the theoretical foundation of opaque predicates (with references to papers providing deeper technical explanations), the practical implementation using ASM, and finally the results after compiling and running the tool.

Opaque Predicates

Before jumping to the implementation, we now briefly explain what opaque predicates are. A predicate is an expression whose result is a boolean value true or false. Given that result, a program takes one action or another (e.g. this would be the condition provided to an if/else statement, or to a switch statement). Usually, a programmer provides a simple expression, or the result from a call to another method, etc. Through static analysis it is not very complex to discern which results lead to which paths.

The idea behind an opaque predicate is to replace a predicate P with a more complex expression whose output is known at protection time, but difficult to extract by a static analysis, or when using a deobfuscator. More information about this protection can be found in the original work by Collberg et al. A Taxonomy of Obfuscating Transformations.

For example, consider this simple code:

x = getCurrentTimestamp();

y = x * 2;

if ((y * y - 4 * x * x) == 0) { // For every possible input: (2x)² - 4x² = 4x² - 4x² = 0

performCriticalOperation();

} else {

corruptData(); // Never executes

}

Even if this is a very simple example, it is necessary to understand the theory previously explained. In this code, we want to always call the performCriticalOperation method, but don't want to make it so easy to see for both static analysis and deobfuscators. Adding opaque-predicate makes the predicate not easy to understand at first sight, but always evaluates true so the performCriticalOperation method is always called.

Opaque-Predicate Protection Implementation

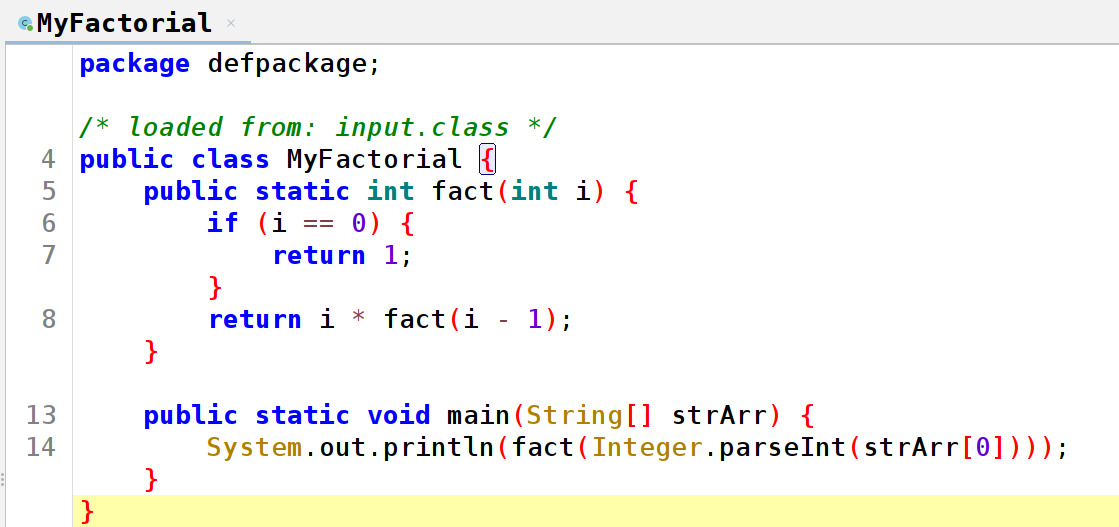

Although the last time I had programmed in Java was during my bachelor's degree (I didn't even have Java programming in my skills on my CV), I decided to give it a try and write the obfuscation in Java using the ASM library. Here is the class and method I had to obfuscate:

public class MyFactorial {

public static int fact(int n) {

if(n == 0)

return 1;

int res = n * fact(n-1);

return res;

}

public static void main(String[] args)

{

System.out.println(fact(Integer.parseInt(args[0])));

}

}

I decided to have something generic, a list of obfuscation passes with a transform method, that would allow me to call them as a pipeline of protections. Although simple, I created an interface with that method to implement:

public interface ObfuscatorTransformer {

void transform(MethodNode node);

}

The idea is simple: a manager maintains a list of ObfuscatorTransformer objects and applies each transformer's transform method sequentially to every method, with each transformer modifying the MethodNode in turn. A more complete model would maintain analysis metadata, support transformations at the ClassNode level, and provide additional context that transformers could leverage during their passes.

Next, I wrote a class that implemented the previous interface for the opaque predicate transformation. This class accepted the name of the method and the method descriptor as parameters in the constructor:

public MethodObfuscator(String method_name, String method_descriptor) {

this.method_name = method_name;

this.method_descriptor = method_descriptor;

}

The obfuscation uses these values to look for the method to protect; any other method is just skipped in the transform method:

public void transform(MethodNode node) {

if (!node.name.equals(method_name) || !node.desc.equals(method_descriptor)) {

log.debug("Method {} with descriptor {}, doesn't match", node.name, node.desc);

return;

}

Back then, my approach was to look for the invoke instruction that calls the method recursively, and then look for the LabelNode that represents the block by searching backward. With experience, my approach today would be quite different, for example, generating a control-flow graph (CFG), looking for the block where to add the opaque predicate, and finally manipulating the CFG to create the fake block and adding the obfuscated condition before the if instruction.

InsnList insns = node.instructions;

ListIterator<AbstractInsnNode> it = insns.iterator();

while (it.hasNext()) {

AbstractInsnNode ins = it.next();

if (!(ins instanceof MethodInsnNode))

continue;

MethodInsnNode invoke = (MethodInsnNode) ins;

if (!invoke.desc.equals(method_descriptor))

continue;

boolean found_label = false;

AbstractInsnNode ln = null;

while (it.hasPrevious()) {

ln = it.previous();

if (ln instanceof LabelNode) {

found_label = true;

break;

}

}

if (!found_label)

return;

FrameNode stack_frame = (FrameNode) ln.getNext().getNext();

insns.insert(stack_frame, generate_opaque_predicate((LabelNode) ln, node, stack_frame));

break;

}

Once we have found the invoke instruction to protect, we look for the beginning of the basic block that contains it. With that information, and the FrameNode which contains all the information about the memory layout in that part of the method (number of locals, number of stack slots, etc.), we then generate the opaque predicate and add the basic block as one of the landing blocks from the not so conditional code.

The next code calls a generate_opaque_predicate method that generates an InsnList with the opaque predicate expression. An InsnList is a doubly linked list from ASM that provides useful methods for retrieving instructions and inserting them in different locations; also, we can insert a whole InsnList somewhere in another list of instructions. The generator method simply generates a complex expression, and transforms the expression into a list of instructions that generate ASM objects for producing the correct bytecode.

Generating the conditional code is simple: we just need to create a new LabelNode and then add it wherever we want it to be present in the bytecode. We don't need to add it once the label is created; we can create the label and add it afterward. That allows us to create the if construction by providing the label as the place to jump to in case the condition is met.

private InsnList generate_opaque_predicate(LabelNode ln, MethodNode mn, FrameNode fn) {

InsnList opaque_predicate = new InsnList();

LabelNode recursive_call_label = new LabelNode();

/// variables used in the opaque predicate

LocalVariableNode n1 = new LocalVariableNode("n1", "I", "I", ln, recursive_call_label, mn.maxLocals);

LocalVariableNode n2 = new LocalVariableNode("n2", "I", "I", ln, recursive_call_label, mn.maxLocals+1);

LocalVariableNode n3 = new LocalVariableNode("n3", "I", "I", ln, recursive_call_label, mn.maxLocals+2);

LocalVariableNode n4 = new LocalVariableNode("n4", "I", "I", ln, recursive_call_label, mn.maxLocals+3);

/// generate an opaque predicate, this expression can be

/// more complex in order to make reverse engineering more difficult

opaque_predicate.insert(generate_internal_opaque_predicate(mn, n1, n2, n3, n4));

log.debug("Introducing a fake conditional jump to factorial code");

/// after inserting the obfuscated code, insert the jump code

opaque_predicate.add(new JumpInsnNode(Opcodes.IFNE, recursive_call_label));

/// create a few instructions in the block that will never run

/// this part could be improved to make it look more legit.

log.debug("Including instructions that are never executed");

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n3.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n4.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IMUL));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ISTORE, 1));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, 1));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IRETURN));

log.debug("Introducing final label and stack frame");

/// now the call to the function

opaque_predicate.add(recursive_call_label);

/// Although I tried using the flag F_SAME to generate the same stack

/// frame as the previous one (".stack same" in Java bytecode), the frame

/// is not properly created. The next instruction adds a new frame with

/// the same information as the previous one.

opaque_predicate.add(

new FrameNode(Opcodes.F_NEW, fn.local.size(), fn.local.toArray(), fn.stack.size(), fn.stack.toArray()));

return opaque_predicate;

}

The opaque predicate uses four local variables; we need to create them, and they can be used throughout the whole method. The values for the locals are generated from the current maximum number of locals, so we make sure no other part of the code has stored any value there. The local values are all 32-bit size, so for each int value we have one local variable slot, and if we had a long value, we would need to use two local variable slots.

Next, we generate the opaque predicate and add it to the list of instructions. This leaves a value on the stack that we can directly compare using the IFNE instruction. When the condition is met, it jumps to the recursive call. This is the block we always want to jump to, so as mentioned at the beginning, we know the result at obfuscation time. But it is difficult to guess for an analyst or for an automatic deobfuscation tool. We also generate some code for the block that will never run; this code could be made more obfuscated in order to give fewer hints about the opaque predicate and make it look more legitimate. The last part of the code generates a new frame with the memory information. At that moment I was not really sure about the ASM API, but this can be left to ASM to be calculated automatically (it's important to leave these memory frames correct to avoid headache problems due to all the Java memory checks).

Here is the whole code of generate_internal_opaque_predicate that it is used to generate the obfuscated expression (see the Java-generated expression at the end of the post):

private InsnList generate_internal_opaque_predicate(MethodNode mn,

LocalVariableNode n1,

LocalVariableNode n2,

LocalVariableNode n3,

LocalVariableNode n4)

{

InsnList opaque_predicate = new InsnList();

log.debug("Generating the opaque predicate");

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.ICONST_5));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ISTORE, n1.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new IntInsnNode(Opcodes.BIPUSH, 10));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ISTORE, n2.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.ICONST_0));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ISTORE, n3.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.ICONST_0));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ISTORE, n4.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n2.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n1.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.ICONST_M1));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IXOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.DUP));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ISTORE, n3.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(134348928));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IAND));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(270585864));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n1.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(134348928));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IAND));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(17367588));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IADD));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(422302381));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IXOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.ISHR));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n3.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(4194304));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IAND));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(1813135624));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n1.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(4194304));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IAND));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(-1845424011));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IADD));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(-28094082));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IXOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IREM));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n3.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(537919494));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IAND));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(100929616));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n1.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(537919494));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IAND));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(136382728));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IADD));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(775231835));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IXOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n3.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(1209143309));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IAND));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(297232));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n1.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(1209143309));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IAND));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(20996224));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IADD));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(1230436755));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IXOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n4.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(-2147166719));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IAND));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(285220928));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n2.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(-2147166719));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IAND));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(1207959690));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IADD));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(-653986101));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IXOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n1.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n2.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.ICONST_M1));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IXOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.DUP));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ISTORE, n4.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(297795840));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IAND));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(603987978));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n2.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(297795840));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IAND));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(35690496));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IADD));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(937474315));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IXOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.ISHL));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.ISUB));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IAND));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n3.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(-851443701));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IAND));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(302055936));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n1.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(-851443701));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IAND));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(269440));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IADD));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(549118304));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IXOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IXOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n4.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(679510656));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IAND));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(84283648));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n2.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(679510656));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IAND));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(268517402));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IADD));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(1032311705));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IXOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IDIV));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n4.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(33554432));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IAND));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(-2134896314));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new VarInsnNode(Opcodes.ILOAD, n2.index));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(33554432));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IAND));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(939870240));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IADD));

opaque_predicate.add(new LdcInsnNode(-1161471636));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IXOR));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IMUL));

opaque_predicate.add(new InsnNode(Opcodes.IADD));

return opaque_predicate;

}

The MethodObfuscator is used from an ObfuscatorManager. This ObfuscatorManager reads the class file and goes over all the methods, calling the transform method from MethodObfuscator. Another method exists for dumping the class file back from memory to disk once the method has been modified:

public void supply(Path class_file) throws IOException

{

if (!class_file.toString().toLowerCase().endsWith(EXTENSION))

{

log.warn("Expected a .class extension, {} incorrect file", class_file.getFileName());

return;

}

log.debug("Starting obfuscation of file {}: ", class_file.getFileName());

byte[] class_file_bytes = Files.readAllBytes(class_file);

/// create the class node for later

ClassNode cls_node = new ClassNode();

/// create the class reader with the bytes from the file.

ClassReader cls_reader = new ClassReader(class_file_bytes);

/// now read the file, and call the Transformation with the methods

cls_reader.accept(cls_node, read_flags);

/// go over each one of the methods and look for the

/// one we want to obfuscate

List<MethodNode> methods = cls_node.methods;

log.debug("Number of methods in the class: {}", methods.size());

for (int i = 0; i < methods.size(); i++)

obf.transform(methods.get(i));

stored_node = cls_node;

}

Once we have all these pieces, we can pack them all together with a Main class that provides a very simple CLI interface.

Compiling and Testing the Project

The project has a maven pom.xml to compile it, and the simple class to try it out. We can call mvn package in the root of the project:

$ mvn package

[INFO] Scanning for projects...

...

[INFO] ------------------------------------------------------------------------

[INFO] BUILD SUCCESS

[INFO] ------------------------------------------------------------------------

[INFO] Total time: 2.516 s

[INFO] Finished at: 2026-01-27T12:54:05+01:00

[INFO] ------------------------------------------------------------------------

Next, we can get the help from the command line with -h:

$ java -jar target/exampleobfuscator.jar -h

usage: java -jar exampleobfuscator.jar [-c <arg>] [-d <arg>] [-h] [-m

<arg>] [-o <arg>] [-v]

-c,--class <arg> Class file to obfuscate

-d,--descriptor <arg> Descriptor of method to obfuscate

-h,--help Show this help message

-m,--method <arg> Method name to obfuscate

-o,--output <arg> Output file where to write obfuscated

-v,--verbose Increase verbosity

Finally, we call the tool with the right arguments to obfuscate the test class file:

$ java -jar target/exampleobfuscator.jar -c test/input.class -m fact -d "(I)I" -o MyFactorial.class -v

12:54:22.434 [main] DEBUG obfuscator-manager - Starting obfuscation of file input.class:

12:54:22.444 [main] DEBUG obfuscator-manager - Number of methods in the class: 3

12:54:22.444 [main] DEBUG MethodObfuscator - Method <init> with descriptor ()V, doesn't match

12:54:22.444 [main] DEBUG MethodObfuscator - Analyzing method, looking for recursive calls

12:54:22.444 [main] DEBUG MethodObfuscator - Method for obfuscation found, looking for label where to insert obfuscation...

12:54:22.445 [main] DEBUG MethodObfuscator - Generating the opaque predicate

12:54:22.445 [main] DEBUG MethodObfuscator - Introducing a fake conditional jump to factorial code

12:54:22.445 [main] DEBUG MethodObfuscator - Including instructions that are never executed

12:54:22.445 [main] DEBUG MethodObfuscator - Introducing final label and stack frame

12:54:22.445 [main] DEBUG MethodObfuscator - Method main with descriptor ([Ljava/lang/String;)V, doesn't match

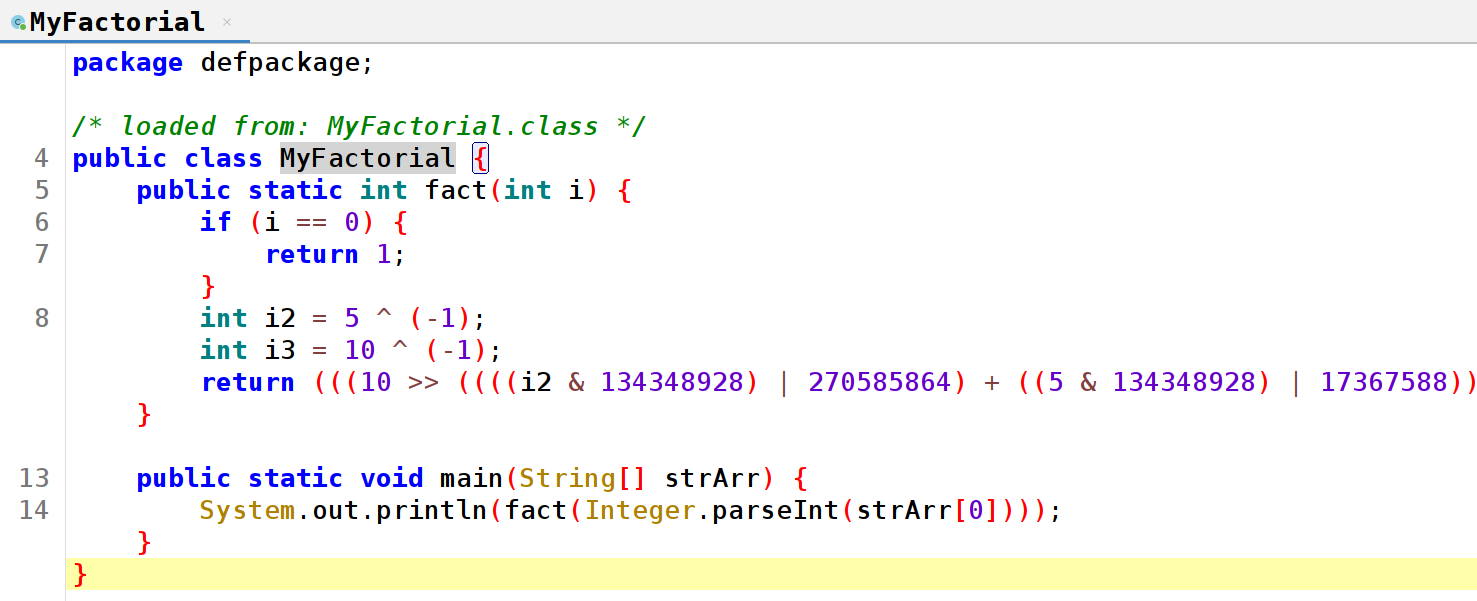

The tool has found the method, and it has modified it. Next with jadx we can see the non-obfuscated, and the obfuscated version:

Here is the complete line from the obfuscated version that cannot be seen in the picture:

return (((10 >> ((((i2 & 134348928) | 270585864) + ((5 & 134348928) | 17367588)) ^ 422302381)) % ((((i2 & 4194304) | 1813135624) + ((5 & 4194304) | (-1845424011))) ^ (-28094082))) | ((((i2 & 537919494) | 100929616) + ((5 & 537919494) | 136382728)) ^ 775231835)) + ((((((((i2 & 1209143309) | 297232) + ((5 & 1209143309) | 20996224)) ^ 1230436755) & (((((0 & (-2147166719)) | 285220928) + ((10 & (-2147166719)) | 1207959690)) ^ (-653986101)) - (5 << ((((i3 & 297795840) | 603987978) + ((10 & 297795840) | 35690496)) ^ 937474315)))) ^ ((((i2 & (-851443701)) | 302055936) + ((5 & (-851443701)) | 269440)) ^ 549118304)) / ((((i3 & 679510656) | 84283648) + ((10 & 679510656) | 268517402)) ^ 1032311705)) * ((((i3 & 33554432) | (-2134896314)) + ((10 & 33554432) | 939870240)) ^ (-1161471636))) == 0 ? i2 * i3 : i * fact(i - 1);

There are a few improvements that should be done here for making the bytecode less readable and to better hide which code would run after the expression is evaluated. For example, each part of the conditionally run blocks should be obfuscated, and the call to the fact method should be replaced by a reflective call, making it harder to see the semantics of each part.

Last Words

This challenge that I had to solve was a good first step to move into the world of Java bytecode obfuscation. As I mentioned at the beginning, Java bytecode is easy to reverse engineer as the bytecode provides enough information for reconstructing the properties from the original source code. For that reason, it is important to protect it against static analyses like decompilation, using protectors that make the code hard to read. Also, the use of ASM, although it needs higher abstraction constructions for simplifying its usage, does all the internal work for manipulation of the bytecode and generation of new class files (although sometimes this part becomes a headache when we have to manipulate stack and local memory because ASM strictly checks that the memory layout is correct).

Looking back on this challenge and my time at Quarkslab so far, I've learned not just about bytecode manipulation, but also about the complexity of the software protection landscape. As companies develop new and sophisticated software protections to prevent analysis, analysts continue to create newer tools and techniques to bypass these defenses. This creates an ongoing cat-and-mouse game between obfuscation and deobfuscation (as stated in my last paper). For anyone interested in getting started with bytecode manipulation, I'd recommend starting small with ASM's Tree API, becoming comfortable with the bytecode instruction set, and gradually working on increasingly complex transformations.

Acknowledgments

I want to thank all the QShield team for the chance I had to work with them writing and developing obfuscations for Java, always leading me toward better software practices that are helping me to improve. To Jean François who asked me to look for a topic to write a post and told me that it was a good idea to write about this small challenge. To Ivan who contacted me after the EuroLLVM conference and told me that it would be a good idea to apply for the position in QShield.