Author Francis Gabriel

Category Reverse-Engineering

Tags OLLVM, obfuscation, Miasm, symbolic execution, reverse-engineering, 2014

We recently looked at the Obfuscator-LLVM project in order to test its different protections. Here are our results, and explanations on how we deal with obfuscation.

Introduction

As we sometimes have to deal with heavily obfuscated code, we wanted to have a look at the Obfuscator-LLVM project to check the strengths and weaknesses of the generated obfuscated code. We looked at the latest version available (based on LLVM 3.5). We will show how it is possible to break all the protections using the Miasm reverse engineering framework.

Warning: this article only shows a method among others to break the OLLVM obfuscation passes. Although it contains many code samples, it is not a Miasm tutorial and there is no all-in-one Python script to download at the end. Of course, we could make a huge article, where we would analyze a complex program obfuscated by OLLVM, on an unsupported Miasm architecture... but no. We keep things simple and show how we manage to cleanup the code.

First, we present all the tools we used and then, how it is possible on a simple example application we made, to break all OLLVM layers one by one (then all together).

Disclaimer: Quarkslab also works on obfuscation using LLVM. We work on that topic on both part, attacking obfuscation or designing some. These results are not yet public, and not ready to be made public. So, we looked at OLLVM because we know the challenges faced here. OLLVM is a useful project in the obfuscation world where everything is about (misplaced) secrets.

Quickly: What is obfuscation?

Code obfuscation means code protection. A piece of code which is obfuscated is modified in order to be harder to understand. As example, it is often used in DRM (Digital Rights Management) software to protect multimedia content by hiding secrets informations like algorithms and encryption keys.

When you need obfuscation, it means everybody can access your code or binary program but you don't want some to understand how it works. It is security through obscurity and a matter of time before someone can break it. So the security of an obfuscation tool depends on the time an attacker must spend in order to break it.

Used Tools

Test Case

Our target is a single function which does some computations on the input value. There are 4 conditions which also depend on the input parameter. The application is compiled for x86 32-bit architecture:

unsigned int target_function(unsigned int n)

{

unsigned int mod = n % 4;

unsigned int result = 0;

if (mod == 0) result = (n | 0xBAAAD0BF) * (2 ^ n);

else if (mod == 1) result = (n & 0xBAAAD0BF) * (3 + n);

else if (mod == 2) result = (n ^ 0xBAAAD0BF) * (4 | n);

else result = (n + 0xBAAAD0BF) * (5 & n);

return result;

}

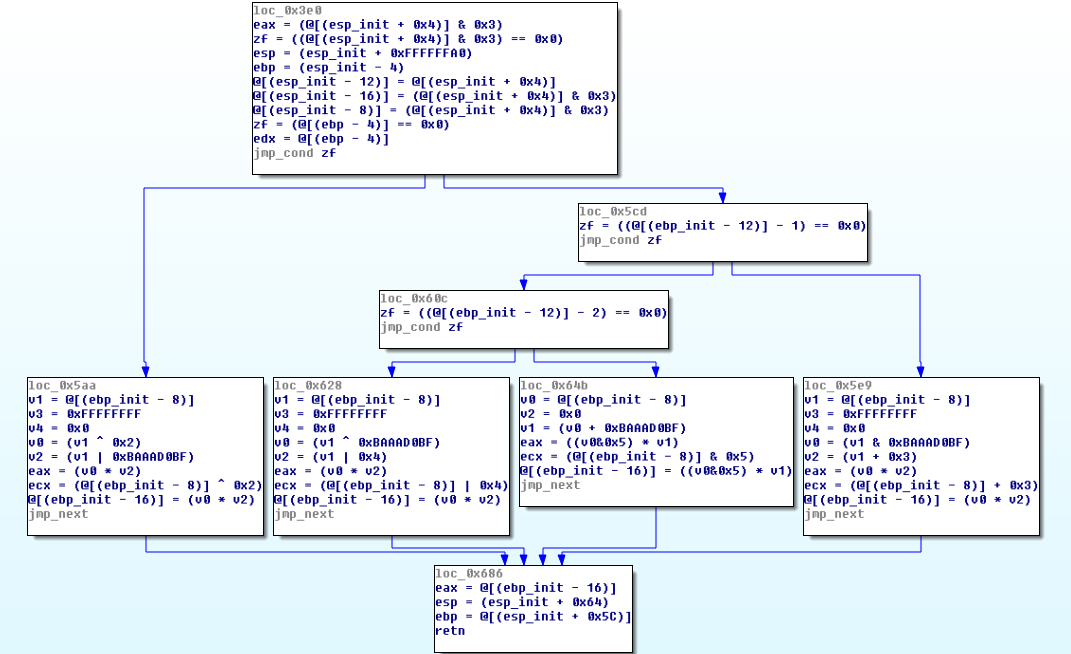

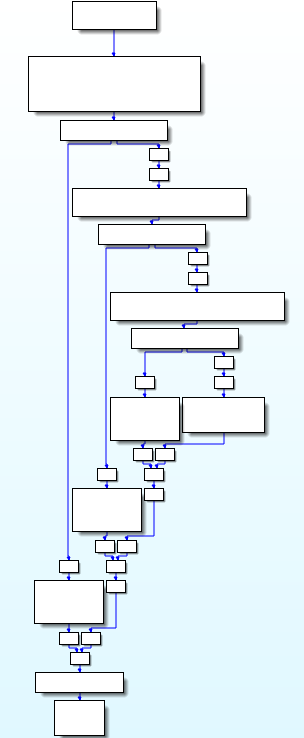

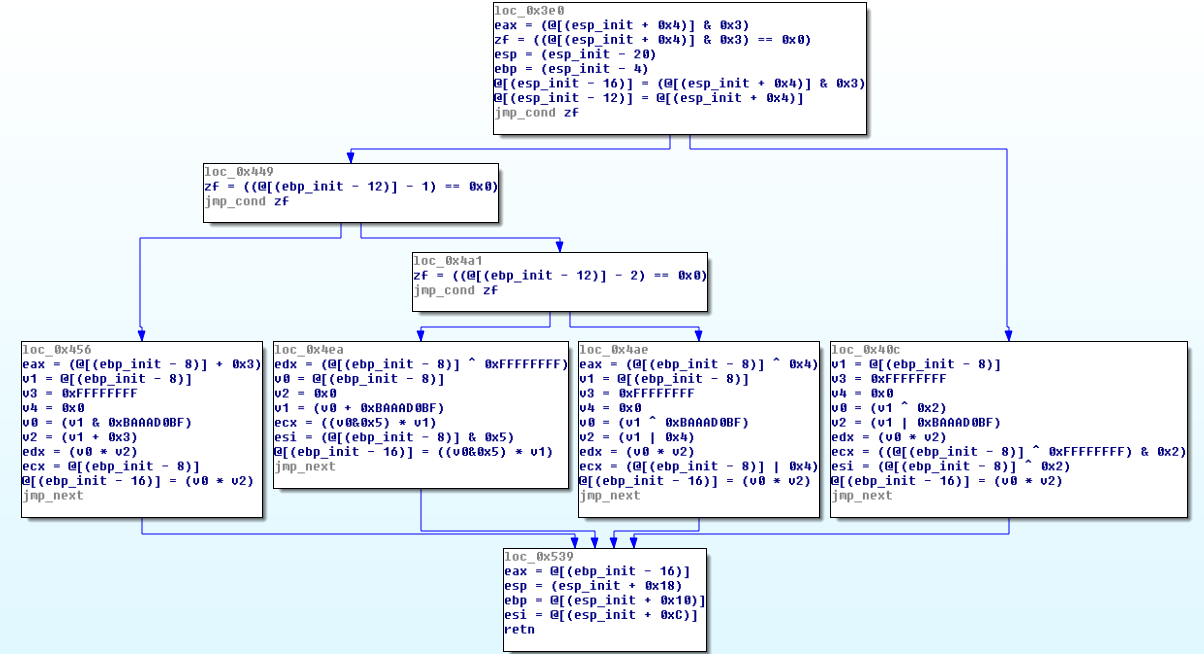

Here is the IDA Pro Control Flow Graph representation:

We can see there are 3 conditions and 4 paths which make a specific computation using boolean and arithmetic instructions. We made it this way so that all OLLVM passes can obfuscate something in the test program.

This function is very simple because it is the best way to learn. Our goal is not to obtain a 100% generic deobfuscation tool but to study OLLVM behaviour.

Miasm Framework

Miasm is a Python open source reverse engineering framework. The latest version is available here: https://github.com/cea-sec/miasm. As we said earlier, this article is not a Miasm tutorial although we'll show some pieces of code. Other tools can be used to do what we did, but this article is a good opportunity to show that this framework is evolving day by day and can be used to make powerful deobfuscation tools.

Warning! As the Miasm API can change in future commits, it is important to note the examples we give here are valid with the latest Miasm version available at the release date of this article (commit a5397cee9bacc81224f786f9a62adf3de5c99c87).

Graph Representation

Before we can start to analyze the obfuscated code, it is important to decide the deobfuscated output representation we want. It is not an easy problem because deobfuscation work can take some time and we want to have an understandable output.

We could translate basic blocks content into LLVM Intermediate Representation in order to recompile them, and apply optimisation passes to clean the useless parts of code and obtain a new binary, but it is time consuming and it could be done as a future improvement. Instead, we choose to build our deobfuscated output in an IDAPython graph, using GraphViewer class. This way we can build nodes and edges easily and fill the basic blocks with the Miasm intermediate representation.

As an example, here is the graph our script produces on our un-obfuscated test case we presented earlier:

Sure, there are still some efforts to make for the output to be more understandable, but that's enough for this article. On the above screenshot, we can see the 3 conditions and the 4 paths with their respective computation. The graph could not be valid in terms of execution but it leaves enough information for the analyst to understand the function properly. And that's all deobfuscation is about.

Our script used to produce the graph is ugly, there is no colors/cosmetics in the basic blocks. Also this is not 100% Miasm IR code because it is not easy to read. We choose to convert the IR to some (near Python) pseudo-code instead.

So, when we do some deobfuscation work and want to display the result, we can generate the output using this representation and compare it to the above screenshot, as it is the original one.

Breaking OLLVM

Quick Presentation

We will not explain in details how OLLVM works because it is already very well explained from the project website (http://o-llvm.org). But quickly, we can say it is composed of 3 distinct protections: Control Flow Flattening, Bogus Control Flow and Instructions Substitution, which can be cumulated in order to make the code very complicated to statically understand. In this part, we show how we managed to remove each protection, one by one and then all together.

Control Flow Flattening

This pass is explained here: https://github.com/obfuscator-llvm/obfuscator/wiki/Control-Flow-Flattening

We applied this pass using the following command line on our test case application:

../build/bin/clang -m32 target.c -o target_flat -mllvm -fla -mllvm -perFLA=100

This command enables the Control Flow Flattening protection on all the functions of our binary so that we are sure our test function is targeted.

Protected Function

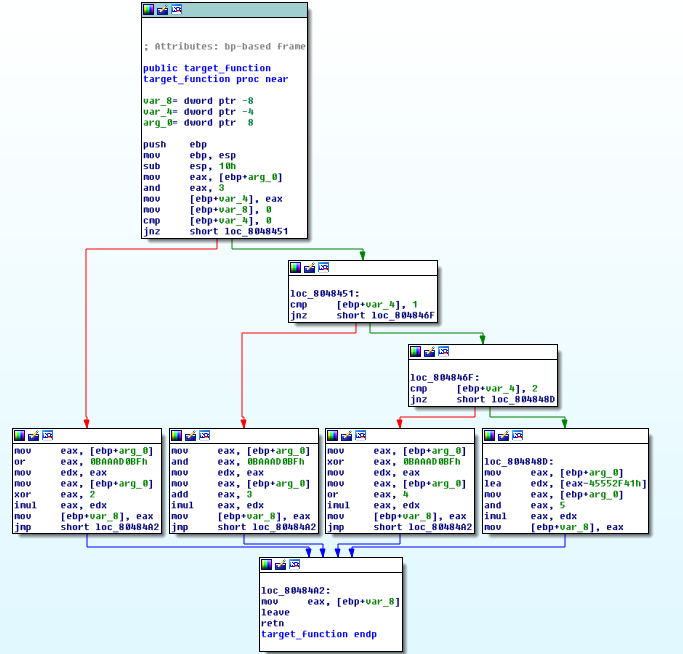

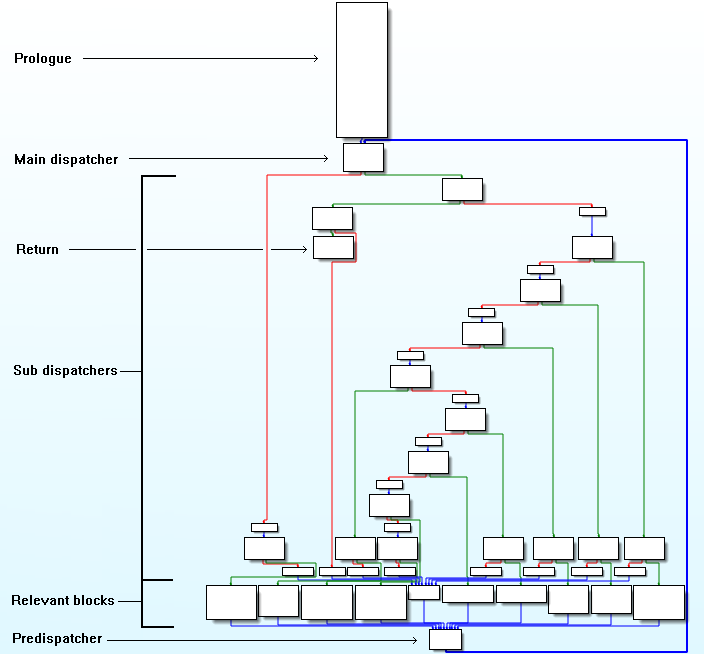

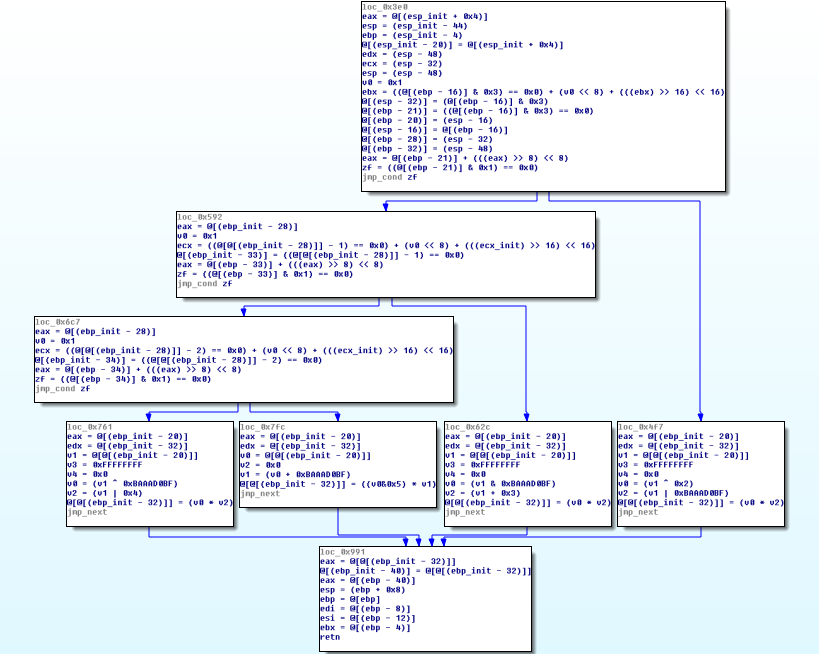

By looking at the control flow graph of our target function in IDA, one can see:

The behaviour of the obfuscated code is quite simple. On the prologue, a state variable is affected with a numeric constant which indicates to the main dispatcher (and to sub-dispatchers) the path to take to reach the target relevant basic block. The relevant blocks are the ones of the original un-obfuscated function. At the end of each relevant basic block, the state variable is affected with another numeric constant to indicate the next relevant block, and so on.

The original conditions are transformed to CMOV conditional instructions, and according to the result of the comparison they will set the next relevant block in the state variable.

This pass doesn't add any protection at the instruction level, so the code still remains readable. Only the control flow graph is destroyed. Our goal here is to recover the original CFG of the function. We need to recover all possible paths, meaning we need to know all the links (parent -> child) between relevants basic blocks in order to rebuild the flow.

Here we require a symbolic execution tool which will browse the code and try to compute each basic block destination. If a condition occurs, it will give us the test and the possible destinations list. The Miasm framework has a symbolic execution engine (for x86 32-bit architecture and some others) based on its own IR and a disassembler to convert binary code to it.

Below is documented Miasm Python code which enables us to do symbolic execution on a basic block in order to compute its destination address:

# Imports from Miasm framework

from miasm2.core.bin_stream import bin_stream_str

from miasm2.arch.x86.disasm import dis_x86_32

from miasm2.arch.x86.ira import ir_a_x86_32

from miasm2.arch.x86.regs import all_regs_ids, all_regs_ids_init

from miasm2.ir.symbexec import symbexec

from miasm2.expression.simplifications import expr_simp

# Binary path and offset of the target function

offset = 0x3e0

fname = "../src/target"

# Get Miasm's binary stream

bin_file = open(fname).read()

bin_stream = bin_stream_str(bin_file)

# Disassemble blocks of the function at 'offset'

mdis = dis_x86_32(bin_stream)

disasm = mdis.dis_multibloc(offset)

# Create target IR object and add all basic blocks to it

ir = ir_a_x86_32(mdis.symbol_pool)

for bbl in disasm: ir.add_bloc(bbl)

# Init our symbols with all architecture known registers

symbols_init = {}

for i, r in enumerate(all_regs_ids):

symbols_init[r] = all_regs_ids_init[i]

# Create symbolic execution engine

symb = symbexec(ir, symbols_init)

# Get the block we want and emulate it

# We obtain the address of the next block to execute

block = ir.get_bloc(offset)

nxt_addr = symb.emulbloc(block)

# Run the Miasm's simplification engine on the next

# address to be sure to have the simplest expression

simp_addr = expr_simp(nxt_addr)

# The simp_addr variable is an integer expression (next basic block offset)

if isinstance(simp_addr, ExprInt):

print("Jump on next basic block: %s" % simp_addr)

# The simp_addr variable is a condition expression

elif isinstance(simp_addr, ExprCond):

branch1 = simp_addr.src1

branch2 = simp_addr.src2

print("Condition: %s or %s" % (branch1,branch2))

The code above is an example of just one basic block symbolic execution. In order to cover all the function's basic blocks, we can use it by starting at the prologue of the target function and follow the execution flow. If we encounter a condition we must explore all branches, one by one, until we cover the function entirely.

So we must have a branches stack to process the next available one when we reach the return of the function. For each branch we have to save the state in order to restore all the symbolic execution context (the registers for instance) when we want to process it.

Intermediate Function

By applying the previously explained method, we are able to rebuild an intermediate CFG. Let's display it with our graph representation script:

In this intermediate function, all the useful basic blocks and the conditions are now visible. Although the main dispatcher and its sub-dispatchers are useful for the execution of the code, they are useless for us because we just want to recover the original CFG. So we need to remove them, which is equivalent to keep only relevants blocks.

In order to do that, we can use the constant "shape" of OLLVM control flow flattening. Indeed, most of the relevants blocks (excepted the prologue and return basic block), are located at a very precise place we can detect. We have to start from the original protected function and make some coding to build a generic algorithm which will find the relevants blocks:

Start from the function prologue (which is relevant)

We are on the main dispatcher. Get its parent (different of prologue): it is the pre-dispatcher

Mark as relevant all pre-dispatcher parents

Mark as relevant the only block which has no child(ren): the return block

This algorithm can easily be realized statically, by using the Miasm disassembler which gives us, as we seen earlier, the list of all disassembled basic blocks of the target function. Once we get the relevant blocks list, we are able to rebuild the original control flow by following the rules of this algorithm during the symbolic execution:

Define a variable which contains parent block (prologue at start) (only relevant blocks can be affected to this variable)

On each new block we encounter, if it is in relevant list we can do the link between it and the parent block. Set this new block as parent.

On each condition, each path will have its own relevant parent block variable

And so on.

In order to illustrate this algorithm, below is a documented example:

# Here we disassemble target function and collect relevants blocks

# Collapsed for clarity but nothing complicated here, and the algorithm is given above

relevants = get_relevants_blocks()

# Control flow dictionnary {parent: set(childs)}

flow = {}

# Init flow dictionnary with empty sets of childs

for r in relevants: flow[r] = set()

# Start loop of symbolic execution

while True:

block_state = # Get next block state to emulate

# Get current branch parameters

# "parent_addr" is the parent block variable se seen earlier

# "symb" is the context (symbols) of the current branch

parent_addr, block_addr, symb = block_state

# If it is a relevant block

if block_addr in flow:

# We avoid the prologue's parent, as it doesn't exist

if parent_addr != ExprInt32(prologue_parent):

# Do the link between the block and its relevant parent

flow[parent_addr].add(block_addr)

# Then we set the block as the new relevant parent

parent_addr = block_addr

# Finally, we can emulate the next block and so on.

Bogus Control Flow

This pass is explained here: https://github.com/obfuscator-llvm/obfuscator/wiki/Bogus-Control-Flow

We applied this pass using the following command line, on our test case application:

../build/bin/clang -m32 target.c -o target_flat -mllvm -bcf -mllvm -boguscf-prob=100 -mllvm -boguscf-loop=1

This command enables the Bogus Control Flow protection on all the functions of our test binary. We set only one pass on the "-boguscf-loop" parameter because it does not change the problem, the generation and the recovery are just much slower, and more RAM is needed when the pass is applied.

Protected Function

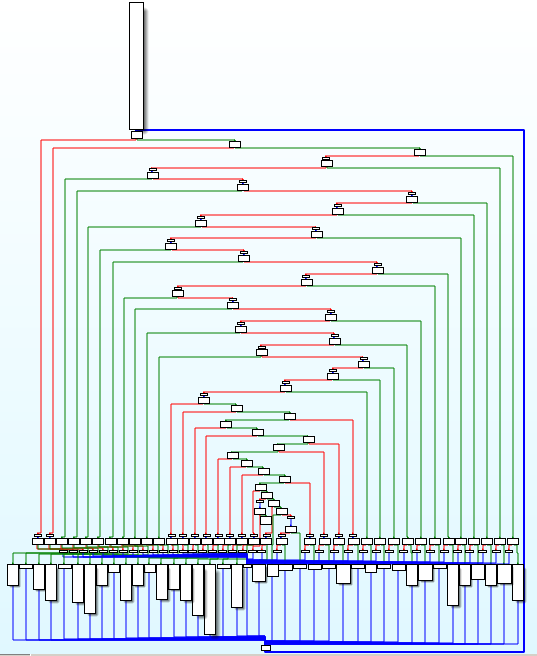

Here is the control flow graph IDA Pro gives us when we load our target binary:

The poor resolution is not important here as this picture is enough to see the function is complex to understand. This pass, for each basic block to obfuscate, creates a new one containing an opaque predicate which makes a conditional jump: it can lead to the real basic block or another one containing junk code.

We could use the symbolic execution method we seen in the previous part. By applying this method we'll find all useful basic block and rebuild the flow. But there is a problem: the opaque predicate. The basic block containing junk code returns to it's parent, so if we follow this path during symbolic execution, we'll get stuck in an infinite loop. So, we need to solve the opaque predicate in order to directly find the right path and avoid the useless block.

Here is a graphical explanation of the problem, which is available in the source code of OLLVM:

// Before :

// entry

// |

// ______v______

// | Original |

// |_____________|

// |

// v

// return

//

// After :

// entry

// |

// ____v_____

// |condition*| (false)

// |__________|----+

// (true)| |

// | |

// ______v______ |

// +-->| Original* | |

// | |_____________| (true)

// | (false)| !-----------> return

// | ______v______ |

// | | Altered |<--!

// | |_____________|

// |__________|

//

// * The results of these terminator's branch's conditions are always true, but these predicates are

// opacificated. For this, we declare two global values: x and y, and replace the FCMP_TRUE

// predicate with (y < 10 || x * (x + 1) % 2 == 0) (this could be improved, as the global

// values give a hint on where are the opaque predicates)

During our symbolic execution, we need to simplify the following opaque predicate: (y < 10 || x * (x + 1) % 2 == 0). Miasm can still help us to do that because it contains an expression simplification engine which operates on its own IR. We have to add the knowledge of the opaque predicate. As we have an "or" (||) between two equations and as the result has to be True it is enough to only simplify one.

The goal here is to do pattern matching using Miasm and replace the expression: x * (x + 1) % 2 by zero. So, the right term of the opaque predicate is True and we solve it easily.

It seems the ollvm developers made a little mistake in the code comments above: the announced opaque predicate is not valid. At first, we didn't managed to match it using the Miasm simplification engine. By looking at the equations given by Miasm we saw that the opaque predicate equation was: (x * (x - 1) % 2 == 0) (minus one instead of plus one).

This problem can be verified by looking at the OLLVM source code:

BogusControlFlow.cpp:620

//if y < 10 || x*(x+1) % 2 == 0

opX = new LoadInst ((Value *)x, "", (*i));

opY = new LoadInst ((Value *)y, "", (*i));

op = BinaryOperator::Create(Instruction::Sub, (Value *)opX,

ConstantInt::get(Type::getInt32Ty(M.getContext()), 1,

false), "", (*i));

This piece of code shows the problem. The comment indicates (x+1) but the code is using Instruction::Sub directive which means: (x-1). As we work modulo 2, it is not a real problem because the result of the equation is the same, but working with pattern matching make this information important.

Since we know precisely what we have to match, here is a code example to do it using Miasm:

# Imports from Miasm framework

from miasm2.expression.expression import *

from miasm2.expression.simplifications import expr_simp

# We define our jokers to match expressions

jok1 = ExprId("jok1")

jok2 = ExprId("jok2")

# Our custom expression simplification callback

# We are searching: (x * (x - 1) % 2)

def simp_opaque_bcf(e_s, e):

# Trying to match (a * b) % 2

to_match = ((jok1 * jok2)[0:32] & ExprInt32(1))

result = MatchExpr(e,to_match,[jok1,jok2,jok3])

if (result is False) or (result == {}):

return e # Doesn't match. Return unmodified expression

# Interesting candidate, try to be more precise

# Verifies that b == (a - 1)

mult_term1 = expr_simp(result[jok1][0:32])

mult_term2 = expr_simp(result[jok2][0:32])

if mult_term2 != (mult_term1 + ExprInt(uint32(-1))):

return e # Doesn't match. Return unmodified expression

# Matched the opaque predicate, return 0

return ExprInt32(0)

# We add our custom callback to Miasm default simplification engine

# The expr_simp object is an instance of ExpressionSimplifier class

simplifications = {ExprOp : [simp_opaque_bcf]}

expr_simp.enable_passes(simplifications)

Then, every time we call: expr_simp(e) (with "e" a lambda Miasm IR expression), if the opaque predicate is contained in it, it will be simplified. Since Miasm IR classes sometimes call expr_simp() method, it is possible that the callback is executed during IR manupulations.

Intermediate Function

Now, we have to apply the same symbolic execution algorithm than before, without dealing with relevants blocks. Indeed, useless blocks will automatically be removed since they are not executed. We obtain the follow CFG:

To get this graph, we just added the opaque predicate knowledge to our algorithm, and Miasm simplified it. The symbolic execution finds all possible paths and ignore impossible ones. We can see the "shape" of the function is correct but the result is kind of ugly because of the remaining instructions added by OLLVM and some empty basic blocks.

Recovered Function

We can now apply the same heuristics than before (Control Flow Flattening) in order to clean the remains. Ok, it is an ugly method but we have to find something which works since we cannot use compiler simplification passes. We obtain the following CFG, which is pretty much the same as the original one:

Original code is recovered. We can see the 3 conditions and the 4 equations that are used to compute the output value.

Instructions Substitution

This pass is explained here: https://github.com/obfuscator-llvm/obfuscator/wiki/Instructions-Substitution

We applied this pass using the following command line, on our test case application:

../build/bin/clang -m32 target.c -o target_flat -mllvm -sub

This command enables the Instructions Substitution protection on all the functions of our test binary.

Protected Function

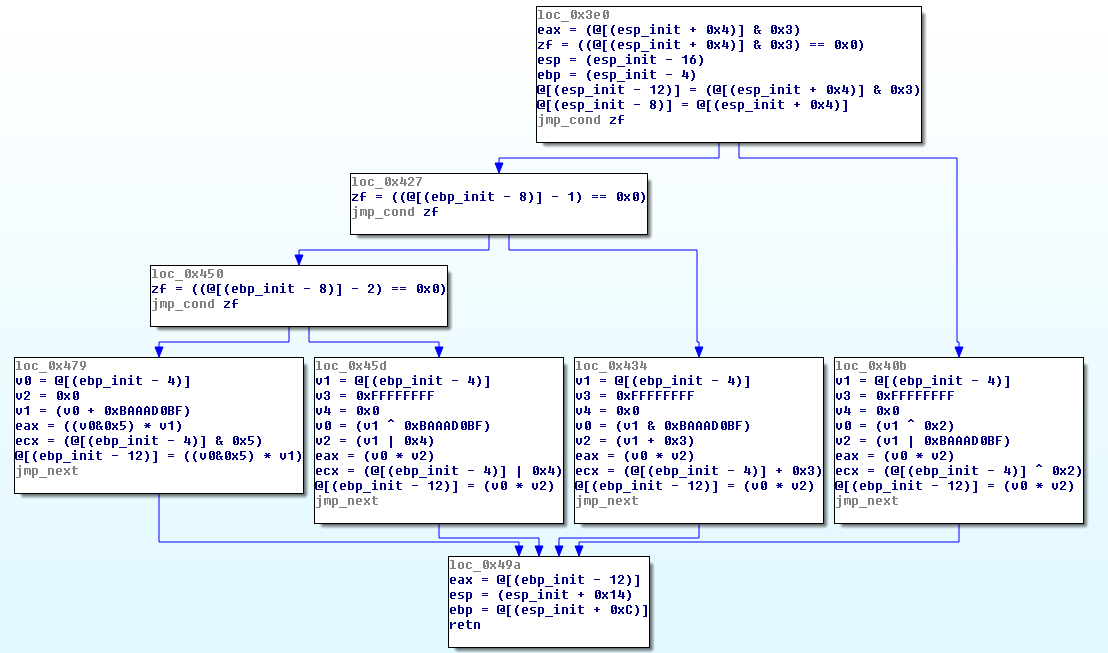

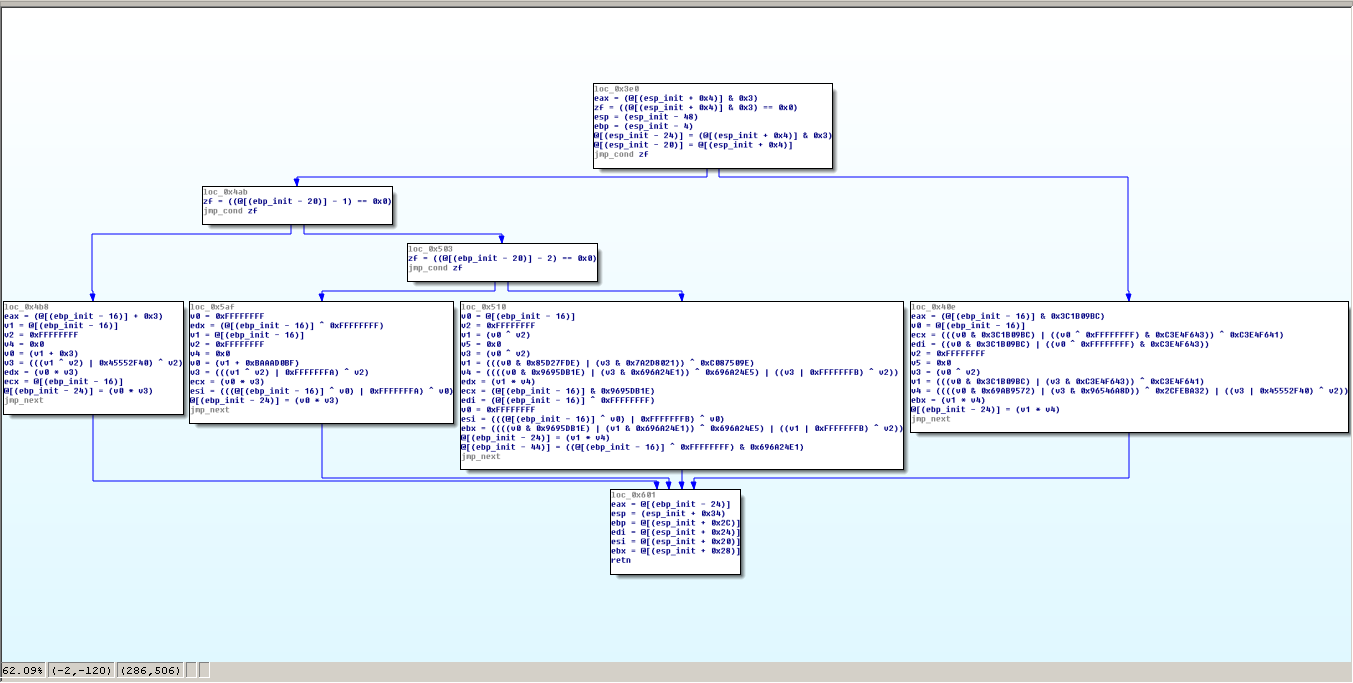

Since this protection doesn't modify the original CFG, it is interesting to display it directly in our graph representation, using Miasm IR:

As expected, the function "shape" hasn't changed, we can still see conditions but the relevants blocks, which are supposed to do computations on input value seems bigger and more complex. Of course, in this example they are not very impressive since it is a simple one but it can be very ugly on a longer original code.

OLLVM pass replaced arithmetic and boolean operations by more complex ones. But since it is nothing more than a list of equivalent expressions, we can still attack them by using Miasm pattern matching technique.

As we can see on the OLLVM website, there are several possible substitutions depending on the operator: + , - , ^ , | , &

Here is the code that enables us to simplify the OLLVM XOR substitution:

# Imports from Miasm framework

from miasm2.expression.expression import *

from miasm2.expression.simplifications import expr_simp

# We define our jokers to match expressions

jok1 = ExprId("jok1")

jok2 = ExprId("jok2")

jok3 = ExprId("jok3")

jok4 = ExprId("jok4")

# Our custom expression simplification callback

# We are searching: (~a & b) | (a & ~b)

def simp_ollvm_XOR(e_s, e):

# First we try to match (a & b) | (c & d)

to_match = (jok1 & jok2) | (jok3 & jok4)

result = MatchExpr(e,to_match,[jok1,jok2,jok3,jok4])

if (result is False) or (result == {}):

return e # Doesn't match. Return unmodified expression

# Check that ~a == c

if expr_simp(~result[jok1]) != result[jok3]:

return e # Doesn't match. Return unmodified expression

# Check that b == ~d

if result[jok2] != expr_simp(~result[jok4]):

return e # Doesn't match. Return unmodified expression

# Expression matched. Return a ^ d

return expr_simp(result[jok1]^result[jok4])

# We add our custom callback to Miasm default simplification engine

# The expr_simp object is an instance of ExpressionSimplifier

simplifications = {ExprOp : [simp_ollvm_XOR]}

expr_simp.enable_passes(simplifications)

The method is exactly the same for all substitutions. We just have to check if Miasm is matching it correctly. It could be a little tricky or time consuming because Miasm may suffer of some matching problems sometimes and we have to match specifically some equations. But when it's done... it's done.

Also, it is important to say we have an advantage here because the obfuscator we are analyzing is open-source and we just have to look at the source in order to know precisely the substitutions. In a close source obfuscator, we have to find them manually and it can be very time consuming.

Recovered Function

Once the knowledge of all OLLVM substitutions is added to the Miasm simplification engine, we can regenerate the CFG:

We can see on the screenshot above the relevants basic blocks are smaller and cleaned from ugly equations. Instead, we have the original equations back, and it is understandable for an analyst.

Full Protection

It is a good point to break all protections one by one but often, the power of an obfuscator is to be able to cumulate passes, which makes the code very hard to understand without manipulation. Also, in real life, people may want to enable the maximum protection level in order to obfuscate their software. So, it is important to be able to handle all the protections at the same time.

We enabled the maximum OLLVM protection level on our test case function using this command:

../build/bin/clang -m32 target.c -o target_flat -mllvm -bcf -mllvm -boguscf-prob=100 -mllvm -boguscf-loop=1 -mllvm -sub -mllvm -fla -mllvm -perFLA=100

Protected Function

By looking at the protected function in IDA, one can see the following control flow graph:

It is important to say that passes cumulation seems to significantly improve the protection level of the code because opaque predicates can be transformed by instructions substitution and the control flow flattening is applied on a bogus control flow protected code. On the screenshot above, we can see more and longer relevant blocks.

Recovered Function

But we just run our script containing all methods described in this article, without any modification. The function is completely recovered and although the protected function above seems very impressive, we can say here the cumulation of all the passes doesn't make any difference, at the protection level.

We can see some useless lines our heuristic cleanup script didn't remove but it is negligeable as we recovered the original "shape", conditions and equations of the original function.

Bonus

As we have seen, it is possible to attack directly the control flow graph in order to rebuild it and fill it with understandable pseudo code. On our test case we can understand the code differently, using only Miasm symbolic execution engine.

We know that our function take one input parameter and produce an output value, which depends on the input. What we can do is, during symbolic execution, each time we reach the bottom (return) of a branch, to display EAX equation (which is the return value register for x86 32-bit architecture). For this example, we activated the full OLLVM protections options as we've seen in the previous part of this article.

# .. Here we have to do basic blocks symbolic execution, as we seen earlier ..

# Jump to next basic block

if isinstance(simp_addr, ExprInt):

# Useless code removed here...

# Condition

elif isinstance(simp_addr, ExprCond):

# Useless code removed here...

# Next basic block address is in memory

# Ugly way: Our function only do that on return, by reading return value on the stack

elif isinstance(simp_addr, ExprMem):

print("-"*30)

print("Reached return ! Result equation is:")

# Get the equation of EAX in symbols

# "my_sanitize" is our function used to display Miasm IR "properly"

eq = str(my_sanitize(symb.symbols[ExprId("EAX",32)]))

# Replace input argument memory deref by "x" to be more understandable

eq = eq.replace("@32[(ESP_init+0x4)]","x")

print("Equation = %s" % eq)

By using the code above and running the symbolic execution, we get the following output:

starting symbolic execution...

------------------------------

Reached return ! Result equation is:

Equation = ((x^0x2) * (x|0xBAAAD0BF) & 0xffffffff)

------------------------------

Reached return ! Result equation is:

Equation = ((x&0xBAAAD0BF) * (x+0x3) & 0xffffffff)

------------------------------

Reached return ! Result equation is:

Equation = ((x^0xBAAAD0BF) * (x|0x4) & 0xffffffff)

------------------------------

Reached return ! Result equation is:

Equation = ((x&0x5) * (x+0xBAAAD0BF) & 0xffffffff)

------------------------------

symbolic execution is done.

Great, the result is exactly what we can find in the source code of our test case application!

Conclusion

Although our script is a good start, it doesn't and will never break all functions protected by OLLVM, because on one hand there are always particular cases depending on the target binary and the scripts have to be patched/hacked/improved accordingly. Also it relies on Miasm which can have some unsupported features we have to implement or report.

We tested this script on more complex functions, with loops for instance and it is working pretty well. But it does not handle particular cases, for example when a loop stop condition depends on an input parameter. It is difficult to handle because we have to deal with already encountered branches and quickly enter an infinite symbolic execution loop. In order to detect them, we have to do branches states differences to deduce the stop condition and continue symbolic execution normally.

The OLLVM project is really interesting and useful because it shows by the example how to manipulate LLVM in order to build your own obfuscator, which can support several CPU architectures. Compared to commercial closed-source protections, we have seen having access to the source code helps to break protections. But it also shows how strongly obfuscation relies on secrets: how the transformations are applied, on what rely transformations, how they are combined and so on. So, really, congrats to OLLVM team for exposing that.

Conversely to what many people believe, code obfuscation is REALLY difficult. It is not about forbidding access to the code and data, it is about buying time and thinking ahead of how one will break your layers of protection.

Thanks

OLLVM authors for their useful project

Fabrice Desclaux for the awesome Miasm framework

Camille Mougey for his contribution and help on Miasm

Ninon Eyrolles for her help and corrections